SONNET 60

Like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore,

So do our minutes hasten to their end;

Each changing place with that which goes before,

In sequent toil all forwards do contend.

Nativity, once in the main of light,

Crawls to maturity, wherewith being crown'd,

Crooked eclipses 'gainst his glory fight,

And Time, that gave, doth now his gift confound.

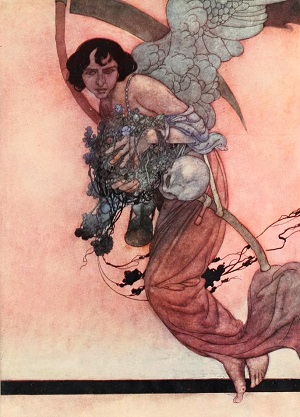

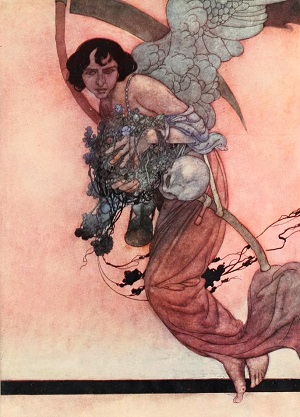

Time doth transfix the flourish set on youth,

And delves the parallels in beauty's brow,

Feeds on the rarities of nature's truth,

And nothing stands but for his scythe to mow.

And yet to times in hope my verse shall stand,

Praising thy worth, despite his cruel hand.

NOTES

LX. This Sonnet is in connection with that next before. It is also under the influence of the melancholy cast of thought not perhaps unnaturally produced by the theory of an unvarying and inexorable succession, a revolution ever the same. The particulars which make up human life succeed one another in unvarying order and with unresting onward movement, from birth to maturity, and from maturity to decay and dissolution. But the poet anticipates

greater durability for his verse, and consequently for the fame of his friend. Lix. and lx. probably constitute a separate group.

5. The main of light. The expanse of light; the world conceived as though a wide ocean enlightened by the rays of the sun.

6. Crawls to maturity. Meaning, probably, not merely that the progress

is slow, but that the condition of mankind is abject. Cf. Hamlet, Act

iii. sc. i, lines 129-131, "What should such fellows as I do crawling between earth and heaven?"

7. Crooked eclipses. Adverse circumstances and conditions, which are

"crooked," as being hostile to onward progress, changing its course, or

arresting it.

8. Doth now his gift confound. Spoil and render worthless his gift.

Cf. v. 6.

9. Doth transfix the flourish set on youth. Doth kill and destroy youthful beauty.

11. Feeds on, &c. Feeds on whatever is pre-eminently excellent.

Nature's truth. That which is naturally and genuinely beautiful and

excellent, as opposed to what is meretricious and artificial.

How to cite this article:

Shakespeare, William. Sonnets. Ed. Thomas Tyler. London: D. Nutt, 1890. Shakespeare Online. 28 Dec. 2013. < http://www.shakespeare-online.com/sonnets/60.html >.

______

Even More...

Stratford School Days: What Did Shakespeare Read? Stratford School Days: What Did Shakespeare Read?

Games in Shakespeare's England [A-L] Games in Shakespeare's England [A-L]

Games in Shakespeare's England [M-Z] Games in Shakespeare's England [M-Z]

An Elizabethan Christmas An Elizabethan Christmas

Clothing in Elizabethan England Clothing in Elizabethan England

Queen Elizabeth: Shakespeare's Patron Queen Elizabeth: Shakespeare's Patron

King James I of England: Shakespeare's Patron King James I of England: Shakespeare's Patron

The Earl of Southampton: Shakespeare's Patron The Earl of Southampton: Shakespeare's Patron

Going to a Play in Elizabethan London Going to a Play in Elizabethan London

Ben Jonson and the Decline of the Drama Ben Jonson and the Decline of the Drama

Religion in Shakespeare's England Religion in Shakespeare's England

Alchemy and Astrology in Shakespeare's Day Alchemy and Astrology in Shakespeare's Day

Entertainment in Elizabethan England Entertainment in Elizabethan England

London's First Public Playhouse London's First Public Playhouse

Shakespeare Hits the Big Time Shakespeare Hits the Big Time

|

More to Explore

Introduction to

Shakespeare's Sonnets Introduction to

Shakespeare's Sonnets

Theories on the Intent of the Sonnets Theories on the Intent of the Sonnets

Shakespearean Sonnet

Style Shakespearean Sonnet

Style

How to Analyze a Shakespearean Sonnet How to Analyze a Shakespearean Sonnet

The Rules of Shakespearean Sonnets The Rules of Shakespearean Sonnets

Shakespeare's Sonnets: Q & A Shakespeare's Sonnets: Q & A

Are Shakespeare's Sonnets Autobiographical? Are Shakespeare's Sonnets Autobiographical?

Petrarch's Influence on Shakespeare Petrarch's Influence on Shakespeare

Themes in Shakespeare's Sonnets Themes in Shakespeare's Sonnets

Shakespeare's Greatest Love Poem Shakespeare's Greatest Love Poem

Shakespeare and the Earl of Southampton Shakespeare and the Earl of Southampton

The Order of the Sonnets The Order of the Sonnets

The Date of the Sonnets The Date of the Sonnets

Who was Mr. W. H.? Who was Mr. W. H.?

Are all the Sonnets addressed to two Persons? Are all the Sonnets addressed to two Persons?

Who was The Rival Poet? Who was The Rival Poet?

Publishing in Elizabethan England Publishing in Elizabethan England

Shakespeare's Audience Shakespeare's Audience

_____

|

On Sonnets 55 to 66 ... "Eleven miscellaneous, loosely-linked verses, tracing the course of friendship, its dreads and jealousies. The

friend has become an ideal, and in faithfulness to that ideal lies the poet's hope of immortality and that "his verse

shall stand." He dreads the ravages of time, but fame will keep him ever young. In his present state of gloom and despair he would die, but death

now would mean oblivion, and he cannot "leave his love alone." These Sonnets are much more allegorical than

personal, and describe the poet's yearning for immortality far more than his human affection for a human being." John Cuming Walters. (The Mystery of Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: New Century Press.)

|

_____

Shakespeare's Greatest Metaphors Shakespeare's Greatest Metaphors

Shakespeare's Metaphors and Similes Shakespeare's Metaphors and Similes

Shakespeare on Jealousy Shakespeare on Jealousy

Shakespeare on Lawyers Shakespeare on Lawyers

Shakespeare on Lust Shakespeare on Lust

Shakespeare on Marriage Shakespeare on Marriage

_____

|

A Look at Metaphors ... "Metaphors are of two kinds, viz. Radical, when a word or root of some general meaning is employed with reference to diverse objects on account of an idea of some similarity between them, just as the adjective 'dull' is used with reference to light, edged tools, polished surfaces, colours, sounds, pains, wits, and social functions; and Poetical, where a word of specialized use in a certain context is used in another context in which it is literally inappropriate, through some similarity in function or relation, as 'the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune', where 'slings' and 'arrows', words of specialized meaning in the context of ballistics, are transferred to a context of fortune." Percival Vivian. Read on...

|

_____

Portraits of Shakespeare Portraits of Shakespeare

Shakespeare's Contemporaries Shakespeare's Contemporaries

Shakespeare's Sexuality Shakespeare's Sexuality

Worst Diseases in Shakespeare's London Worst Diseases in Shakespeare's London

Shakespeare on the Seasons Shakespeare on the Seasons

Shakespeare on Sleep Shakespeare on Sleep

|