| directory |

| home | contact |

|

|||||||||||||||

| search | |||||||||||||||

Shakespeare's Fairies: The Triumph of Dramatic ArtFrom Shakespeare's Comedy of A Midsummer-night's Dream. Ed. William J. Rolfe. New York: American Book Company.Demetrius and Lysander, Helena and Hermia, are but slight sketches, imperfectly individualized, though not without distinctive traits which the critics have seldom troubled themselves to point out. They are, however, inferior — the women in particular — to characters of the same class in Love's Labour's Lost and The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Hence some of the critics have assumed that this play must be of earlier date than those — which, on other grounds, is clearly impossible, though the Dream appears to contain scattered remnants of very early work. The fact is, Shakespeare was but slightly interested in the human characters of the present play, with the exception of Theseus and Bottom. It was the fairies who chiefly attracted him, and on whom he lavished the wealth of his genius. They have been aptly called "the favourite children of his romantic fancy"; and perhaps, as Drake remarks, "in no part of his works has he exhibited a more creative and visionary pencil, or a finer tone of enthusiasm, than in bodying forth these 'airy nothings,' and in giving them, in brighter and ever-durable tints, once more "a local habitation and a name." Shakespeare's delineation of these little creatures is one of the most remarkable triumphs of his dramatic art. They are not diminutive human beings with superhuman powers, though in some respects they are like human children. Like young children before they have learned the distinction between right and wrong, they have no moral sense, and little or no comprehension of such sense in the mortals with whom they are associated. Like children, they live in the present, and are quite incapable of reflection. They think and feel like the child. Their loves and their quarrels are like those of the child. Oberon and Titania quarrel over the possession of the pretty changeling boy as two children do about a toy which they both want; and later, when Titania, fascinated with Bottom, ceases to care for the boy and gives him to Oberon, he gets over his petulance, releases her from the magic influence of the love-juice, and they "make up" and are friends again, like children rather than like lovers.

The tricks they play on the human lovers are like those that children play on one another, without any thought of the suffering they may cause the victims. "Lord, what fools these mortals be!" is Puck's only comment upon the results of his mischief. He is delighted that things befall preposterously, and anticipates more

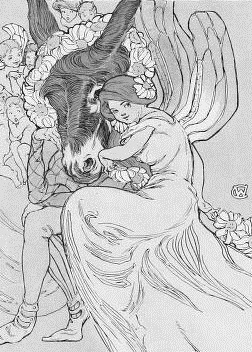

sport when Demetrius and Lysander wake up, for "then will two at once woo one." Titania feels no mortification when she finds that she has been enamoured of Bottom with his ass's head. She only knows that she loathes him now that she has recovered from the infatuation. We cannot help pitying her for the humiliation to

which she has been subjected; but our pity is wasted. She is no more capable of feeling humiliated by any such experience than a child would be after it was over. She forgets it, and never

recalls it.

As I have intimated, Bottom is the only one of the clownish company who demands any special notice. He is English, like his name, and like all of Shakespeare's low-life folk, no matter in what land or what age he places them. Puck calls him "the shallowest thickskin of the barren" set; but how he lords it over them, and how absolutely they submit to his self-conceited domination! Quince is the nominal manager of the play, but Bottom usurps the office. It is only by flattery that Quince, after Bottom has wanted to assume the parts of Thisbe and the lion, persuades him to take that of Pyramus; for "Pyramus is a sweet-faced man; a proper man, as one shall see in a summer's day; a most lovely gentleman-like man: therefore you must needs play Pyramus." It is Bottom who criticises certain things in the tragedy "that will never please," - the killing of Pyramus and the introductiion of that "fearful wild-fowl," the lion, among ladies; and it is he who suggests how these difficulties can be obviated, - by a prologue which shall explain that Pyramus is not Pyramus but Bottom the weaver, and is not killed indeed, and that the lion is no lion but Snug the joiner. It is he also who devises the ingenious expedient of having the wall represented by "some man or other," with "plaster or rough-cast about him to signify wall." When Bottom disappears, his companions decide at once that "the play is marred." It is not possible that it can go on: "you have not a man in all Athens able to discharge Pyramus but he"; he "hath the best wit of any handicraft man in Athens, and the best person too, and he is a very paramour for a sweet voice." At the performance of the play he is the only actor who turns aside from his part to speak to the audience in his own person in reply to Theseus and Demetrius; and, the moment after he is dead, he jumps up, and, again assuming the part of stage-manager, asks Theseus whether it will please him "to see the epilogue or to hear a Bergomask dance." We cannot doubt that in Bottom, in a more broadly humorous way than later in Hamlet's talk with the players, Shakespeare intended a good-natured hit at some of the extravagancies and absurdities of the plays and the actors of his time — the plays in the Ercles vein, with parts to tear a cat in, and actors like Bottom, whose chief humour was for the tyrant, spouting such alliterative rhymes as Bottom gets off:— "The raging rocksand the "Now, die, die, die, die, die!" with which he finally flops on the stage. The clowns' play reminds us of the interlude of The Nine Worthies in the earlier Love's Labour's Lost, where, however, the auditors do not allow the actors so fair a chance, but practically break up the performance before it is finally interrupted by the arrival of the messenger sent to inform the Princess that her father is dead. The point of the burlesque is much the same in both cases. As we finish the play, we feel like saying, with our friend Bottom, "I have had a most rare vision!" Or we ask, with Preciosa in The Spanish Student, — "Is this a dream? O, if it be a dream,For myself, I believe, with Campbell, that Shakespeare must have enjoyed writing it no less than we enjoy reading it. He says: "The play is so purely delicious, so little intermixed with the painful passions from which poetry distils her sterner sweets, so fragrant with hilarity, so bland and yet so bold, that I cannot imagine Shakespeare's mind to have been in any other frame than that of healthful ecstasy when the sparks of inspiration thrilled through his brain in composing it. I have heard, however, an old critic object that Shakespeare might have foreseen it would never be a good acting play; for where could you get actors tiny enough to couch in flower-blossoms? ... But supposing that it never could have been acted, I should only thank Shakespeare the more that he wrote here as a poet and not as a playwright. And as a birth of his imagination, whether it was to suit the stage or not, can we suppose the Poet himself to have been insensible of its worth? Is a mother blind to the beauty of her own child? No! nor could Shakespeare be unconscious that posterity would doat on this, one of his loveliest children. How he must have chuckled and laughed in the act of placing the ass's head on Bottom's shoulders! He must have foretasted the mirth of generations unborn at Titania's doating on the metamorphosed weaver, and on his calling for a repast of sweet peas. His animal spirits must have bounded with the hunter's joy while he wrote Theseus's description of his well-tuned dogs and of the glory of the chase. He must have been happy as Puck himself while he was describing the merry Fairy, and all this time he must have been self-assured that his genius was 'to put a girdle round the earth' and that souls, not yet in being, were to enjoy the revelry of his fancy." How to cite this article:_________ Related Articles

|

|

©1999-2021 Shakespeare Online. All Rights Reserved.