| directory |

| home | contact |

|

|||||||||||||||

| search | |||||||||||||||

King John: Plot SummaryFrom Stories of Shakespeare's English History Plays by Helene Adeline Guerber. New York: Dodd, Mead and company.Act IThe first act opens in the palace of King John, where he is giving an audience to the French ambassador. Summoned to deliver his message, this emissary, after an insulting mention of 'borrowed majesty' calls upon King John of England to surrender to Arthur Plantagenet, son of his elder brother Geffrey, all England, Ireland, and the English possessions in France. When John haughtily inquires what King Philip of France will do in case he refuse, the ambassador rejoins by a formal declaration of war, to which John retorts 'war for war,' warning the ambassador he will be in France almost before his arrival can be announced.The French ambassador having left under safe conduct, Elinor, mother of King John, exclaims she was right in predicting Constance would urge France to war for her son's rights, and reminds John how all could have been settled amicably had he listened to her. Just as John asserts that possession and right are both on his side, — to which his mother does not agree, — the announcement is made that a strange controversy awaits royal decision. Bidding the contestants appear, John mutters that his abbeys and priories will have to bear the expense of the coming expedition to France, ere the two men are ushered in. On questioning them, the King learns one is Robert Faulconbridge, son of a soldier, knighted by his brother Richard, and the other, Philip, illegitimate son of the same knight, who claims inheritance. While both young men are sure they descend from the same mother, Philip the elder expresses doubts in regard to his father, for which Elinor reproves him. Only when he exclaims, however, that he is thankful not to resemble Sir Roger, does Elinor notice his strong resemblance to her son Richard, to which she calls John's attention. Both brothers now begin to plead their cause before the King, interrupting and contradicting one another, the younger claiming how during his father's absence, Richard induced his mother to break her marriage vows. He adds, that aware of her infidelity, the father left all he had to him, cutting off the elder entirely, although John says the law entitles him to a share of Sir Robert's estate, since he was bom in wedlock. Thereupon Robert asks whether his father had no right to dispose of his property as he pleased, while Elinor questions whether Philip would rather be considered the son of Richard Lionheart and forfeit all claim to Faulconbridge, or vice-versa. Thus cornered, Philip confesses he would not resemble his brother or Sir Robert for anjrthing in the world, and when Elinor invites him to forsake all and follow her to France, — where he can win honors in the war, — he joyfully hands over the disputed estates to his brother, and swears he will follow Elinor to the death. Then King John knights Philip, who magnanimously shakes hands with his 'brother by the mother's side,' thus displaying so much of Richard's spirit, that Elinor and John acknowledge him as their kin. All leaving the stage save the new knight, he merrily congratulates himself upon the airs he can now assume, and proposes to fit himself for knightly society by secret practice and by close observation. His soliloquy is interrupted by the entrance of his mother, Lady Faulconbridge, who chides him for speaking disrespectfully of Sir Robert, But, after dismissing her attendant, Philip bluntly informs her that, knowing Sir Robert is not his father, he has renounced all claims to the Faulconbridge estates. After some demur, his mother confesses his surmises have been correct, and that King Richard is indeed his father, whereupon he exclaims, 'Ay, my mother, with all my heart I thank thee for my father! Who lives and dares but say thou didst not well when I was got, I'll send his soul to hell.' This understanding reached, Faulconbridge leads his mother out to introduce her at court, promising to champion her on every occasion.

Act IIThe second act opens in France, before the city of Angiers (Angers), where Austria's forces are drawn up on one side, and the French on the other. Stepping forward, the Dauphin greets 'Austria,' telling young Arthur and his mother Constance, that although once a foe of Richard, Austria is now trying to make amends by helping the rightful heir to his throne. At his request, Arthur embraces this former family foe, freely forgiving him the past, and bespeaking his aid for the future. After the Duke of Austria has pledged himself with a kiss never to abandon Arthur's cause until he has won his rights to England, — 'that white-faced shore, whose foot spurns back the ocean's roaring tides and coops from other lands her islanders,' — Constance effusively promises him a 'mother's thanks, a widow's thanks,' ere King Philip in his turn pledges himself to lay his royal bones before Angiers or compel it to recognise Arthur.Constance is just imploring these champions of her son's rights to await the ambassador's return, with, perchance, favourable news from England, when he appears, bidding French and Austrians hasten to meet the English, who follow close on his heels. This news is immediately confirmed by drum-beats, announcing the approach of the foe, which fact surprises the French and Austrian leaders, although they are ready to welcome them, for 'courage mounteth with occasion.' King John now marches on the stage escorted by his mother, suite, and army, calling down peace upon France provided she yield to his demands, but woe should she resist. His proud address is answered, in kind by King Philip of France, who claims Arthur is the rightful possessor of England, and bids John recognise him as king. Irritated by this demand, John haughtily demands Philip's authority for this claim, only to receive reply that it is made in the name of the Defender of Orphans. When John thereupon taunts Philip for usurping authority, he is charged with that crime himself, ere Elinor and Constance, joining in the quarrel, begin to revile one another hotly, for theirs is a feud of longstanding. In the midst of this quarrel, Elinor vows Arthur is not Geffrey's legitimate son, whereupon Constance indignantly rebukes her, and turning to the lad exclaims his grandmother is trying to cast shame upon him. The quarrel between the women becomes so virulent that the Duke of Austria calls for peace, only to be sneered at by the insolent Faulconbridge, who openly defies him, although Blanch, niece of John, who is also present, evidently admires him. Finally, the French monarch silences the women and disputing nobles, and turning once more to John summons him to surrender the lands he holds to Arthur. After hotly retorting, 'my life as soon: I do defy thee, France,' John invites young Arthur to join him, promising to give him more than France can ever win by force. But, when Elinor tries to coax her grandson to side with them, Constance bitterly suggests his grandmother will give him 'a plum, a cherry, and a fig' in exchange for a kingdom, and by her jibes causes the gentle prince to wail he would rather be dead, than the cause of 'this coil that's made for me.' While Elinor attributes this cry to shame for his mother's conduct, Constance deems it is occasioned by his grandmother's injustice, which diverging opinions rekindle the quarrel, until both monarchs interfere to silence them. Trumpet blasts summoning a deputation from Angiers, end this vituperation, so a citizen, acting as spokesman, demands why they have been summoned to their walls, only to hear both kings claim they have come hither to seek aid to defend the rights of England's King. Addressing the deputation first, King John accuses France of trying to awe them into subjection, whereupon King Philip urges them to remain faithful to their rightful sovereign, adding the threat that should they refuse to obey Arthur, he will compel them to do so. Diplomatically replying they are the King of England's faithful subjects, the spokesman refuses to decide which is the rightful claimant to England's crown, and vows Angiers' gates shall remain closed until the dispute has been duly settled. When King John loudly asserts he is the only rightful bearer of the English crown, - a statement in which he is supported by his nephew Faulconbridge, — the French King urges the citizens not to believe him. Thus starts a new dispute, at the end of which it is decided the question shall be settled by the force of arms, so King Philip brings the momentous interview to a close with the words: 'God and our right!' Shortly after, the French herald, in full panoply, formally summons Angiers to open its gates to Arthur, only to be immediately followed by an English herald, in similar array, demanding admittance for John. To these double summons the men of Angiers respectfully reply they are merely waiting to know which is their lawful sovereign, before they welcome their king. Both monarchs now enter the battlefield with their respective forces, John sarcastically demanding whether France has blood to squander, only to receive as rejoinder from Philip that he will defeat him or die. Impatient to fight, Faulconbridge inquires why they stop to parley, whereupon both kings, raising their voices, bid Angiers state with which party it sides, only to receive the same reply that it is loyal to the King of England. This diplomacy enrages Faulconbridge, who, declaring they are flouting both kings, suggests the besiegers join forces to subdue the insolent rebels, deciding the matter of rightful ownership afterwards. This proposal suits both monarchs, who immediately agree upon the measures to be taken, arranging that the French, English, and Austrians shall attack Angiers from different points. Just as they are about to begin operations, the citizens beg for a hearing, and propose in their turn that John's niece. Lady Blanch, be married to the Dauphin, for whom she would make an ideal wife, vowing 'this union shall do more than battery can,' since they will then fling open their gates to both kings. This proposal fails to please Faulconbridge, who longs for the fray; but Elinor urges John to accept it, which, after Philip calls upon him to speak first, he formally does, stating he will give his niece as dowry all his lands in France, save the town of Angiers. The Dauphin, after expressing eagerness to conclude this match, whispers to Blanch, who in turn signifies maidenly consent. The marriage portion John has promised to bestow upon his niece, proves so enticing to Philip, that he bids the young couple join hands, while the Duke of Austria suggests their betrothal be sealed with a kiss. All preliminaries thus settled. King Philip calls upon Angiers to throw open its gates, so the marriage of the Dauphin and Lady Blanch can be celebrated in St. Mary's chapel, concluding his speech by stating his satisfaction that Arthur and Constance have retired, as the latter would surely object to this arrangement. Then, to satisfy the Dauphin, and French King, who ruefully aver Constance has just cause for displeasure, John proposes to make Arthur Duke of Brittany, and bids a messenger invite him and his mother to the wedding. All now leave the scene save Faulconbridge, who shrewdly comments John has forfeited a small part of his possessions to prevent Arthur from securing the whole, while the King of France has allowed the bribe of a rich alliance for his son to turn him aside from his avowed purpose to uphold the right. He jocosely adds that, as yet, no one has tried to bribe him, but that when the attempt is made, he will immediately 3rield, because, 'since kings break faith upon commodity gain, be my lord, for I will worship thee.'

Act IIIThe third act opens in the tent of the French King, where Constance, having just heard of the royal marriage, exclaims it cannot be true, and threatens to have the Earl of Salisbury punished for trying to deceive her. She pitifully adds that although a widow and prone to fear, she will forgive all, provided he admits he has been jesting, and ceases to cast pitiful glances upon her son. Unable to obey, Salisbury compassionately reiterates he has told the truth, whereupon Constance wails she and her son have been betrayed. In her grief, she bids Salisbury begone, and expresses sorrow when her son implores her to be resigned, saying that were he some monster, she might allow him to be deprived of his rights, but that, seeing his perfections, she cannot endure his being set aside. Before leaving, Salisbury again reminds her she is expected to join both kings, whereupon she vows she will be proud in her grief, and seats herself upon the ground, declaring kings will have to do homage to her, on her throne of sorrows, if they wish to see her.The marriage guests now return from church, King Philip graciously assuring his new-made daughter-in-law that this day shall henceforth be a festival for France, whereupon Constance, rising in wrath from her lowly seat, vehemently declares it shall forever be accursed! When King Philip tells her she has no reason for anger as he will see she gets her rights, she accuses him of betrating her cause, calls wildly upon heaven to defend a widow, and prays that discord may soon arise between these perjured kings, although all present try to silence her. Even the Duke of Austria becomes the butt of her wrath and contempt, for she scornfully bids him don some other garb than the lion's skin on which he prides himself, — an insult he cannot avenge as it is uttered by a woman. Instead, he turns his wrath upon Faulconbridge, when the latter ventures to repeat some of Constance's strictures on royal interference. It is at this moment that the papal legate enters, announcing he has been sent to inquire of John, why, in spite of papal decrees, he refuses to permit Stephen Langton to exercise his office as Archbishop of Canterbury. In return, John denies the Pope's right to call him to account, and vows no Italian priest shall collect tithes in his realm, where he considers himself supreme head under God! His defiant reply smacks of heresy to King Philip, who, venturing to reprove him, is informed that although all other Christian monarchs may submit to the Pope's dictation, be, John, will continue to oppose him, and to consider his friends foes. This statement causes the legate to pronounce John's excommunication, and to declare that anyone taking his life will deserve to be canonised for having performed a meritorious deed. Such a denunciation so pleases Constance, that she adds a few curses addressed to John for depriving her son of his inheritance, until reproved by the legate, who summons Philip to break all alliance with John, since he has forfeited the Pope's regard. Hoping for war, the Duke of Austria sides with the legate, while Faulconbridge taunts him, and King John, Constance, Lewis, and Blanch separately implore Philip to listen to them. All these entreaties merely perplex the French monarch, who, turning to the legate, gravely informs him that having just concluded an alliance with John, it seems an act of sacrilege to break it. He is answered, in a Jesuitical speech, that the Church comes first, and can release from all other vows. While his son and the Duke of Austria urge him to obey the legate's summons, Faulconbridge and Blanch demur, the latter begging husband and father-in-law not to take arms against her uncle. On hearing this, Constance falls upon her knees, appealing to the honour of the King and Dauphin, while Blanch appeals to their love.

The scene closes with Philip's decision to break faith with John and obey the Church, — thereby winning the approval of the legate, his son, and Constance, but incurring the scathing contempt of John, Elinor, and Faulconbridge. Meanwhile poor Blanch sadly wonders with which party she shall side, her relatives and husband now being opposed, and sadly yields when the Dauphin reminds her her first duty is to remain with him. Then, King John, turning to Faulconbridge, bids him summon his army, and defies King Philip, who boldly answers his challenge ere he leaves. The next scene is played on the plain near Angiers, where the battle is raging, and Faulconbridge is seen bearing in triumph the Duke of Austria's head. A moment later, King John appears with his nephew Arthur, whom he has taken prisoner, and now intrusts to the keeping of Hubert, vowing he must hasten back to rescue his mother, who is sorely pressed in her tent. Thereupon Faulconbridge admits he has already delivered Elinor, and adds, 'very little pains will bring this labour to a happy end.' In the next scene the tide of battle sweeps to and fro across the stage, and John is heard informing Elinor and Arthur that they are to remain behind under strong guard, while Faulconbridge will hasten back to England, to wring from the Church new sinews of war, a task so congenial to his violent nature, that he departs vowing 'bell, book, and candle' shall not drive him back. After he has gone, Elinor begins conversing with her grandson, while the King, after lavishing some flattery upon Hubert, informs him he has matters of importance to communicate, which he cannot reveal at present. Seeing Hubert overcome by his condescension, John adds that if it were only midnight, he would dare speak and test his loyalty, — a test Hubert is eager to have applied. Thereupon John bids him keep a watchful eye upon young Arthur, whom he designates as 'a serpent' in his way, hoping this hint will suffice for Hubert to remove the impediment. But, seeing him still obtuse, John proceeds to express himself so plainly, that Hubert assures him Arthur shall not live, and thereby wins eager thanks from the King, who, taking leave of mother and nephew, bids the latter follow Hubert. The next scene is played in the royal French tent, where King Philip, the legate, and Dauphin, are discussing the scattering of an English fleet by a tempest, which damage only partly offsets the loss of Angiers, the seizure of Arthur, and the death of so many brave Frenchmen. The Dauphin is describing how cleverly the English are defending what they have won, when Constance enters, and is pitied by King Philip for the loss of her son. No consolation, however, can touch this bereaved mother, who wildly accuses them all of treachery, and calls for death, in spite of all the King and legate can do to quiet her. When they finally inform her this is madness, she hotly denies it, vowing that were she only insane, she might forget her child or be satisfied with some puppet in his stead, and, as she tears her hair in her grief, Philip notes how grey it has turned, notwithstanding her youth. Appealing to the legate, the poor mother asks in heart-broken tones whether she will see and recognise in heaven the child who was her dearest treasure on earth, and of whom she is so cruelly bereft? In her grief, she eloquently describes the loveliness of her offspring, but pictures him so changed by sorrow and imprisonment that even in heaven his mother will not be able to recognise him. When the King and legate try to soothe her, she vows 'grief fills the room up of my absent child' describing how she misses his constant company and pretty ways, and declares that had they ever experienced a similar loss they would better understand the sorrow which now overwhelms her. Seeing her depart still broken-hearted, Philip follows lest she do herself some injury, while the Dauphin siezes this opportunity to tell the legate that 'bitter shame hath spoiled the sweet world's taste,' for him, because the defeat of the French forces wrankles deep in his heart. Although in reply to fears expressed for Arthur's safety, the Dauphin confidently affirms John will be satisfied in keeping Arthur imprisoned, the legate prophesies that if not dead already, the Prince will soon be slain. Then, he urges the Dauphin to attack England, — to which he has the next right, — before Faulconbridge can raise reinforcements in men and money, using arguments which determine the Dauphin to join him in urging the King to immediate action.

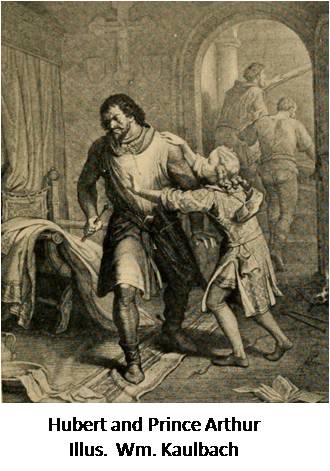

Act IV The fourth act opens in a room in the castle, where Hubert is bidding two executioners heat their irons red-hot, and linger behind the arras until he stamps his foot, when they are to rush forward and bind fast the lad they find in his company. Because one of the men mutters he hopes he is not doing this without warrant, Hubert chides him; then, the men being duly concealed, calls upon Arthur to join him. Entering with a kindly greetftig for his keeper, Arthur, on noticing he is low-spirited, claims he alone has a right to be sorrowful, but that were he only free he would be 'as merry

as the day is long.' He pitifully adds that he is not to blame for being Geffrey's son or heir to England, and that he would gladly be Hubert's child so as to win his love. The fourth act opens in a room in the castle, where Hubert is bidding two executioners heat their irons red-hot, and linger behind the arras until he stamps his foot, when they are to rush forward and bind fast the lad they find in his company. Because one of the men mutters he hopes he is not doing this without warrant, Hubert chides him; then, the men being duly concealed, calls upon Arthur to join him. Entering with a kindly greetftig for his keeper, Arthur, on noticing he is low-spirited, claims he alone has a right to be sorrowful, but that were he only free he would be 'as merry

as the day is long.' He pitifully adds that he is not to blame for being Geffrey's son or heir to England, and that he would gladly be Hubert's child so as to win his love.

This artless talk overcomes the jailor, who exclaims in an aside, that if he converses any longer with such innocence, his 'mercy which lies dead,' will awaken and prevent the execution of his plan. Struck by his unusual pallor, Arthur now touchingly inquires whether Hubert is ill, offering to nurse him because of the love he bears him, a devotion which proves so moving, that with tears trickling down his cheeks, Hubert exhibits the orders he has received, hoarsely asking the Prince whether he can read. After perusing the order, Arthur piteously inquires whether both his eyes will have to be put out with red-hot irons, and wonders whether Hubert will have the heart to do this to the lad, who, when he once had a headache, forfeited his rest to nurse him. When he concludes his eloquent appeal with the words, 'will you put out mine eyes? These eyes that never did nor never shall so much as frown on you,' Hubert grimly insists he must do so, although Arthur vows he would not believe it should an angel state he could be guilty of such cruelty! Steeling his heart against further pleading, Hubert stamps, whereupon the executioners appear with red-hot irons and a rope, ready to carry out his orders. Fleeing to Hubert's arms as his refuge, Arthur piteously clings to him, vowing he will stand still, provided they do not bind him. By such promises, he finally prevails upon Hubert to send the men away, and when they depart, — glad to be spared such work, — he again inquires whether there is no appeal against this awful sentence, describing in feeling terms the distress caused by a mere speck in one's eye, and offering to sacrifice any other member in preference. After a while he notices with relief, that the irons have grown too cold to harm him, and when Hubert mutters they can be reheated, exclaims the fire is nearly extinct, assuring Hubert, when he proposes to rekindle it by blowing upon it, that it will 'blush and glow with shame of your proceedings.' Conquered at last, Hubert exclaims he may keep his eyesight, although he swore to commit this crime. These milder looks and tones relieve Arthur, who cries he appeared like one disguised a while ago, but again resembles himself! To escape the child's fervent gratitude, Hubert departs, vowing John must be made to believe his nephew is dead, and reiterating his promise not to injure Arthur 'for the wealth of all the world,' even though he risk his life! The next scene occurs in King John's palace, where, crowned the second time, he expresses delight at finding himself once more among his people. The Dukes of Pembroke and Salisbury deem this second coronation superfluous, for they declare one might as well 'gild refined gold,' 'paint the lily,' 'throw a perfume on the violet,' as try to enhance the sanctity of a first consecration. But, although both these noblemen plainly deem the ceremony a mistake, John insists he was right in having it performed, ere he graciously inquires what reforms they would like made in state affairs. Speaking in the name of the English people, Pembroke begs John to set Arthur free, for the imprisonment of a child is a great grievance to all his subjects. Just after the King has promised to place Arthur in Pembroke's care, Hubert comes in, and John hastily draws him aside. Meantime, Pembroke exclaims to Salisbury that this is the very man who recently exhibited to one of his friends a cruel warrant which he fears has since been executed. Watching John, therefore, both mark his change of colour, and fancy it bodes ill in regard to Prince Arthur. Then, drawing near them once more, John gravely informs them Arthur is dead, whereupon the lords sarcastically comment upon so opportune an end! Although John tries to defend himself by inquiring whether they think he has command of 'the pulse of life,' they exclaim 'it is apparent foul play,' and take leave of him forever, to go and find the Prince's remains and bury them suitably. Both lords having thus departed in wrath, John regrets what he has done, because 'there is no sure foundation set on blood, no certain life achieved by others' death.' The appearance of a messenger, whose face betokens ill-tidings, causes him to inquire anxiously what news he brings, and when John learns a French force has already landed in England, he wonders why his mother did not warn him. He is then informed how Elinor and Constance have both died within three days of each other, — news which makes his head reel; — still he soon collects himself, and has just found out the Dauphin is leading the French army, when Faulconbridge appears. Exclaiming he can bear no further misfortunes, John demands how his kinsman has prospered, waxing indignant on learning of the defection of his people, many of whom have been influenced by a recent prediction that he will be obliged to relinquish his crown before Ascension Day! Hearing Faulconbridge has brought the prophet with him, John suddenly inquires of this man what induced him to say this, only to be gravely informed he did so 'foreknowing that the truth will fall out so!' In his wrath John entrusts the prophet to Hubert's keeping, with orders to hang him on Ascension Day at noon, and to return to receive further orders as soon as he has placed this unwelcome prophet in safe custody. Hubert and the prophet having gone, John asks Faulconbridge whether he has heard of the landing of the French, of Arthur's death, and of Salisbury's and Pembroke's defection. In hopes of winning the two latter lords back to their allegiance, John orders Faulconbridge to follow them, and only after his departure comments on his mother's sudden death. It is while John is still alone, that Hubert returns, reporting five moons have been seen, which phenomena people connect with Arthur's death. Such is the popular panic in consequence, that its mere description chills John's blood, and makes him turn upon Hubert, accusing him of being alone guilty of Arthur's death, by which he had naught to gain. When Hubert retorts John forced him to commit that crime, the King rejoins, 'it is the curse of kings to be attended by slaves that take their humours for a warrant to break within the bloody house of life.' Thus goaded, Hubert produces the royal warrant, which John no sooner beholds, than he vows murder would never have come to his mind had not so ready a tool been near at hand! When Hubert protests, John angrily inquires why he did not do so when the order was given, as a mere sign would have stopped him, and bids him begone, as one accursed, who has brought down upon England foreign invasion, the disaffection of the nobles, and a panic among the people. This accusation determines Hubert no longer to withhold the information that Arthur still lives, and when he con- cludes with the words it was not in him 'to be butcher of an innocent child,' John, perceiving the political advantage he can draw from this confession, promptly apologises to Hubert, and bids him hasten and tell the news to the peers, whom he invites to join him in his cabinet. The next scene is played before the castle in which Arthur is imprisoned, at the moment when he appears upon the high walls and looks downward, about to spring into space. Before jumping, he implores the ground to be merciful and not hurt him, for, if not crippled by the fall, he hopes to enjoy freedom as a sailor lad. After concluding 'as good to die and go, as die and stay,' Arthur springs, only to expire a moment later on the stones below, gasping they are as hard as his uncle's heart, and imploring heaven to take his soul, and England to keep his bones. When he has expired, Salisbury and Pembroke appear, discuss joining the French, and are overtaken by Faulconbridge, who summons them into the King's presence — summons they disregard, for they never wish to see John again. Advancing, they suddenly descry Arthur's corpse, over which they mourn, pointing it out to Faulconbridge with words of tender pity for the sufferings of the child, and of execration for those who drove him to so desperate an act. Hard-hearted as Faulconbridge is, he agrees 'it is a damned and bloody work,' although he cannot imagine how anyone could be guilty of a child's death. The lords have just registered a solemn oath to avenge Arthur, when Hu- bert appears in the distance, calling out that the Prince is alive and the King wants them, words which seem pure mockery to Salisbury, who harshly bids him begone. As his orders are not immediately obeyed, Salisbury draws his sword, whereupon Faulconbridge restrains him, while Hubert protests that nothing, save irespect for a noble an- tagonist, prevents him from seeking immediate redress for the terms he has used. The rest now turn upon Hubert, terming him murderer, a charge he defies them to prove. Before attacking him, they point to Arthur's corpse as a confirmation of their words, and at the sight of the lifeless Prince, Hlibert truthfully exclaims he left him in good health an hour ago, and protests he 'will weep his date of life out for his sweet life's loss.' But this grief seems pure hypocrisy to Salisbury, who decides to hasten off with his companions to the Dauphin's camp, where, they inform Hubert and Faulconbridge, the King may hereafter send for them. The lords having gone, Faulconbridge demands whether Hubert is in any way to blame for Arthur's death, vowing if he is guilty of slaying a child, no punishment can be too severe for him. When Hubert solemnly swears he is not guilty, 'in act, consent, or sin of thought,' Faulconbridge bids him carry off his little charge, marvelling that England's hopes can make so light and helpless a burden. Then he hastens back to John, for 'a thousand businesses are brief in hand, and heaven itself doth frown upon the land.'

Act VThe fifth act opens in John's palace, just after he has surrendered his crown to the legate, who returns it to him in the Pope's name, accepting him once more as vassal of the holy see. As John has submitted to this humiliation so as to retain possession of the sceptre slipping from his grasp, he implores the legate soon to use his authority to check the advance of the French. After admitting he induced the French to attack England, the legate departs, promising to make them lay down their arms.When he has gone, John inquires whether this is not Ascension Day, exclaiming the prophesy has been fulfilled, since he voluntarily laid aside his crown before noon. It is at this moment Faulconbridge enters, announcing that all Kent save Dover, has already yielded to the French, who have also become masters of London, where the nobles are thronging to receive them. These tidings dismay John, who expected the nobles to return to their allegiance as soon as it became known that Arthur was alive; but, when he learns from Faulconbridge that the little Prince was found dead at the foot of his prison walls, he vehemently exclaims Hubert deceived him! Seeing John hopeless of maintaining his position, Faulconbridge urges him to 'be great in act,' as he has 'been in thought,' suggesting that he fight fire with fire, and by his example infuse courage in everybody. When John rejoins that the legate has promised to make peace with the invader, the Bastard scorns such an inglorious settlement, and bids John arm, lest he lose the opportune moment to triumph over a youthful foe. When he is therefore told to prepare immediately for fight, he goes off with great alacrity. The next scene is played in the French camp, at St. Edmundsbury, where the Dauphin orders copies made of the covenant he has just concluded with the English lords, a covenant which Salisbury promises shall never be broken, although it grieves him to fight his countrymen. The Dauphin has just reassured him in regard to England, — whose prosperity he means to further, — when the legate enters, announcing that John, having concluded peace with Rome, is no longer to be molested. But, loath to relinquish a purpose once avowed, the Dauphin refuses to withdraw at the Church's summons, and claims England as his wife's inheritance, since Arthur is dead. His proud refusal to return to France without having accomplished anything, amazes the legate, who has no time to bring forth further arguments. for trumpets sound and Faulconbridge appears. Demanding whether the legate has been successful, and learning the Dauphin refuses to withdraw, Faulconbridge shows great satisfaction, and reports that his master challenges the French, whom he intends to drive home in disgrace! His defiant speech angers the Dauphin, who, contemptuously remarking it is easy to 'out-scold,' refuses the legate's offers to arbitrate, and informs Faulconbridge his challenge is accepted. The next scene is played on the battle-field, where, meeting Hubert, John eagerly inquires how his troops have fared, and is dismayed to learn Fortune has proved adverse. He is besides, prey to a fever which robs him of strength at the critical moment, so he abandons the field, sending word to Faulconbridge he will take refuge in the neighbouring Abbey of Swinstead. As he is leaving, he learns with delight the Dauphin's supplies have been wrecked on Goodwin Sands, but even such tidings cannot cure him and he turns very faint. In another part of the field, Salisbury, Pembroke and another lord have met, and comment over the number of friends John has' secured, marvelling in particular at Faulconbridge's courage, and wondering whether the King has really left the battle-field. Their conversation is interrupted by a mortally wounded Frenchman, who warns them they are betrayed, and advises them to crave John's pardon before it is too late. On learning that the Dauphin, — who swore friendship with them, — intends to sacrifice them in case he is victorious, all three lords leave the field, bearing with them the wounded man who has so kindly befriended them. In the next scene the Dauphin boasts they have driven the foe from the field, just as a messenger brings word that the English nobles have deserted, and that his supplies have been wrecked! Knowing King John is at Swinstead Abbey, the Dauphin proposes to pursue him thither on the morrow, and retires while his men mount guard over the camp. We now behold Swinstead Abbey, where, coming from opposite directions, Hubert and Faulconbridge meet. In their first surprise they challenge each other, dropping their defiant attitude only when they discover they are both on the English side. Making themselves known, they then eagerly inquire for news; but, it is only after some hesitation that Hubert reveals that John has probably been poisoned by one of the monks, and is now speechless, warning Faulconbridge the end is so near he had better provide for his own safety. Unable to credit such tidings, Faulconbridge inquires further particulars, only to hear the rebel lords have been pardoned and are now with Prince Henry by the royal death-bed. It is in an orchard near this same Abbey that Prince Henry, conversing with Salisbury and another lord, sadly informs them his father's death is imminent. A moment later Pembroke joins them, reporting that the King wishes to be brought out in the open air, as he fancies it will do him good. After giving orders for his father to be conveyed to this spot. Prince Henry laments the sudden seizure which has laid him low; and even while Salisbury is vainly trying to comfort him, bearers bring in the dying monarch. Shortly after gasping, 'Now my soul hath elbow-room.' John adds that an internal fire consumes him! Then, in reply to Prince Henry's inquiries, he admits he is indeed dying from poison, and begs for the relief which no one can afford him, although his sufferings wring tears from all. The sudden appearance of Faulconbridge, rouses John enough to remark he arrives in time to see him die! These tidings dismay Faulconbridge, who announces the Dauphin is coming, and that, having lost most of his own forces, he will not be able to defend his King! At these words John sinks back dead, and Salisbury exclaims: 'My liege! my lord! but now a King, now thus.' Seeing his father has gone, Prince Henry mourns, while Faulconbridge swears he will linger on earth only long enough to avenge John, and will then hasten to wait upon him in heaven as he has done here below. Hearing him add that England is in inuninent danger, Salisbury informs him that the legate has just brought offers of peace from the Dauphin, which can be accepted without shame. Instead of continuing the war, therefore, the Dauphin will retreat to France, leaving the legate to settle terms with Salisbury, Faulconbridge and others. After advising Prince Henry to show his father due respect by attending his body to Worcester, — where John asked to be buried, and where he can assume the English crown, — Faulconbridge promises to serve him faithfully, an oath of fealty in which Salisbury joins. Although Prince Henry can thank them only by tears, the play closes with Faulconbridge's patriotic assurance that 'this England never did, nor never shall, lie at the proud feet of a conqueror,' and that naught will ever make Englishmen afraid as long as 'England to itself do rest but true.'

_________

Related Articles

|

©1999-2021 Shakespeare Online. All Rights Reserved.