| directory |

| home | contact |

|

|||||||||||||||

| search | |||||||||||||||

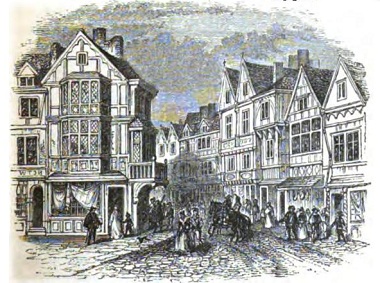

Life in Shakespeare's LondonFrom Shakespeare's London by Henry Thew Stephenson. New York: H. Holt.This people, in a sense, was an ignorant people. Those of the highest rank were well and laboriously educated according to the contemporary standard; but the rank and file paid no attention to learning. They neither read, wrote, nor thought. One today is astonished at the ignorance of the then common people concerning public affairs. Compare a history like Holinshed's with a history like Fronde's or Grardiner's. You find in the former no exposition of principles, no attempt to sift tradition from fact, no sense whatever of the dignity of a thousand page folio in black letter. On the other hand, we read in Holinshed of a terrible storm that killed a dog in Essex, or of a cow that gave birth to a five-legged calf in Kent. Street parades, tiltings, trivial and momentous events alternately, mere gossip, above all, inspired utterances in the form of public proclamations from the crown — this is the sum and substance of Holinshed and Stow — and the people were well satisfied. The matter-of-fact critic of today is too apt to condemn the Elizabethan dramatists for the credulity evinced by their characters. But such criticism is often misplaced. The Elizabethans were credulous people. The opening chapter of Kingsley's Westward Ho! relates a number of foolish inducements held out by Salvation Yeo and John Oxenham, two prospective sailors of the South Seas. But the inducements were not considered foolish then. Kingsley, in his charming way, points a little pleasantly at the inconsistency of English inscriptions upon the wondrous horn of ivory that had been picked up in the land of the Incas. Even here, the amusing sarcasm is slightly misplaced. The Elizabethans would not allow themselves to be troubled by such trifles. The golden city of Monoa was as real to them as Paradise or Hell. The chapter, in fact, is almost a literal transcript of a contemporary pamphlet, doubtless produced in perfect faith. Even Shakespeare, judged by our modern standards, may not have been a really sophisticated man; the ring of truth in Othello's tales to Desdemona may be due to a believing heart. There was going on all the time a rapid change in the social scale. The middle class was rising into prominence. It was no longer necessary to be born a peer in order to become a man of wealth and position. The story of Whittington was repeating itself every day; and, what is more to the point, the people were daily growing more and more proud of the fact. As the age of Elizabeth was the golden time of literature, so it was the golden time of superstition. There was one Banks, a hanger-on of the Earl of Essex, who lived in the Old Bailey and who possessed a wonderful horse named Morocco shod with shoes of silver. This horse could dance to music, count, make answer to questions; do a thousand and one other tricks, among which was his reputed ascent of St. Paul's steeple. London looked upon Banks and his horse as little short of the supernatural; and in later years all London wept at the news from Italy, where both master and horse were burned to death on the charge of sorcery. With this execution the Londoners could heartily sympathize, for they were superstitious to a degree incomprehensible at the present day. None was so ready as Sir Walter Scott himself to acknowledge that the fatal flaw in The Monastery was the demand put upon the credulity of an incredulous people by the introduction of the White Lady of Ayenal. Nothing so well illustrates this difference between the time of Shakespeare and our own as a comparison of the failure of The Monastery and of the success of Hamlet. A serious tragedy based upon a trivial motive is likely to degenerate into out and out farce. Had the audience of Shakespeare believed as we do in regard to superstition, both Hamlet and Macbeth would have probably missed the public approbation. We should certainly think a logic-loving philosopher or an iron-nerved general tainted in his wits, if he allowed his reason to be swayed by a shadowy apparition, or his intrigues to be governed by a trio of vanishing witches; yet Shakespeare was making use of the most powerful motive at his command. Doubtless every person in The Globe play-house shuddered at the appearance of Hamlet's ghost, for it was true, actually true to them, that this might be either Denmark's spirit or the very devil in a pleasing shape.  John Stow, the annalist of England and author of the Survey of London was, next to Camden, the most famous antiquarian student of the age; yet this man, whose Survey is the great store- house of knowledge about Elizabethan London — learned, careful, and methodical — thus interprets the effect of a church struck by lightning: "And here a note of this steeple: as I have oft heard my father report, upon St. James's night, certain men in the loft next under the bells, ringing of a peel, a tempest of lightning and thunder did arise, an ugly-shapen sight appeared to them, coming in at the south window, and lighted on the north, for fear whereof they all fell down, and lay as dead for the time, letting the bells ring and cease of their own accord; when the ringers came to themselves, they found certain stones of the north window to be razed and scratched, as if they had been so much butter, printed with a lion's claw; the same stones were fastened there again and so remain until this day. I have seen them oft, and have put a feather or small stick into the holes where the daws had entered three or four inches deep. At the same time certain main timber posts at Queen-hithe were scratched and cleft from the top to the bottom; and the pulpit cross in Paul's churchyard was likewise scratched, cleft, and overturned. One of the ringers lived in my youth, whom I have often heard to verify the same to be true."The people not only believed in ghosts and witches, but in magic of every sort. Alchemy was a common hobby, and many a man of brain wasted his time and ruined his fortune in the vain search for the philosopher's stone long after the practice had been held up to ridicule upon the stage by Ben Jonson. Astrology, or astronomical fortune-telling, was so thoroughly a factor of the age that every one desired the casting of his horoscope. Leicester consulted Doctor Dee, the astrologer, to discover a propitious date for the Queen's coronation. The great Queen herself consulted him upon an occasion, instead of her family physician, in order to charm away the tooth-ache. Again, a waxen image of Elizabeth was picked up in one of the fields near London. Doctor Dee was immediately sent for to counteract by his charms the evil effect of this familiar kind of sorcery. People, one and all, believed in fairies. The usual critical opinion, that the opening scenes of A Midsummer Night's Dream owe their arrangement to a desire to lead gradually from the real to the unreal, would have caused an Elizabethan to laugh, if not outwardly, in his sleeve. There is nothing unreal about the fairies of that delightful comedy except their size. Any one might not only have seen the pleasant fairies, but also the wicked, and might have become blind by the sight, if he did not take care to protect himself by charms. A grown man did not feel foolish in those days if when in the neighbourhood of a lonely and ghost-haunted wood at night he wore his coat inside out. There were innumerable superstitious rites performed at births, christenings, weddings, on certain days of the year, and in certain places; as, the churchyard, the cross-roads, etc. Every hour in the day, every article in the world — stone, plant, or animal — had its cluster of superstitions. The time was further characterised by a general freedom of manners. We often find personal ridicule and abuse, as well as praise, levelled at individuals from the stage. Different companies and rival play-wrights fought out their private battles on the public boards. A play of ancient setting, such as Hamlet, does not scruple to allude to current events of interest to Londoners. The mob in Romeo and Juliet rallies to the cry of the London 'prentice lads. The actors talked to people in the pit, who in turn pelted an unpopular player from the stage. There existed, likewise, a coarseness of speech in every-day talk that would be quite intolerable to-day. Queen Elizabeth swore like a trooper, spat at her favourites, or threw her slipper at the head of an obdurate councillor. The artificial refinement of our age requires the lines of many of Shakespeare's heroines to be curtailed; yet Beatrice and the like talk no more broadly than did that paragon of female excellence, "Sidney's sister, Pembroke's mother." The great popularity of the stage at once suggests the chief characteristic of the age: artificiality. About the middle of the century appeared Lyly's Euphues. This book, a kind of tale, owed its great vogue to its quaintness of phrase, its antitheses, and its elaborate conceits. The book sold by wholesale. No one was considered fit to appear in public unless he could talk the fustian fashion of the Euphues. The book is intolerably dull to most of us, but the perusal of a few pages will repay the curious, as an object-lesson in the rubbish spoken by the cultivated Elizabethan courtier. Part of the Euphuistic training was the art of compliment. This habit was fostered by the vanity of the Queen. Elizabeth, so some of the foreigners who saw her tell us, possessed several undesirable characteristics, among others a hooked nose and black teeth, and there is no doubt that her skin wrinkled as she grew near seventy. Yet, to the very end of the great Queen's life, the obsequious courtier was welcome who would assure her that he is like to die if he is debarred the sight of that alabaster brow, of those cheeks of rose covered with the bloom of peaches, of those teeth of pearl. Besides the elaborate compliments to the Queen that were frequently introduced into plays and masques, a common custom was to set up a tablet to her honour in the parish church. Here is an example of their inscriptions: "Spain's rod, Rome's ruin, Netherland's relief, Heaven's gem, Barth's joy. World's wonder. Nature's chief. Britain's blessing, England's splendour. Religion's nurse and Faith's Defender."Gossiping was one of the favourite pastimes of the Elizabethans, and London was not yet too large for the practice to be thoroughly effective. Gossip started from the barber-shop and the tavern-table — the Elizabethan equivalent of the afternoon tea — and spread thence in every direction. Space prevents the enumeration of many of the indications of freedom of manner that are to be discovered in every direction. Grossip led to frequent quarrels, that were more hot and bitter because side arms were worn upon all occasions. The fine woman of the time would jostle with the rudest peasants in the pit of the bull-ring and the theatre. Wakes and fairs were of daily occurrence, in which every one joined, irrespective of previous acquaintance. During the yule-tide festivities all distinctions of class were considered as temporarily non-existent. Elizabeth showed herself so often and so intimately to the common people that they considered the acquaintance almost personal. So much for the happy-go-lucky spirit that characterised the time.

The extent of gaming is lamented by all the

contemporary writers who have a leaning towards

reform. Dicing, card playing, and racing, though

to a less extent than the others, were practised

upon every hand; while cheating was but too common. In former times it was considered almost a crime to take interest for money loaned, but by the reign of Elizabeth, this prejudice was so completely overborne that usury was practised by all the money lenders, who did not scruple to turn the screws upon the least occasion.

Related Articles

|

|

©1999-2021 Shakespeare Online. All Rights Reserved.