Shakespeare's Source: The True Chronicle History of King Leir

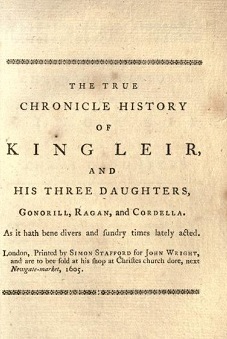

The story of King Lear and his three daughters is an old tale, well known in England for centuries before Shakespeare wrote the definitive play on the subject. The first English account of Lear can be found in the History of the Kings of Britain, written by Geoffrey Monmouth in 1135. Monmouth's account spawned several 16th-century narratives about Lear, including renderings in Holinshed's Chronicles (first edition, 1577) and in The Mirror for Magistrates (1574). Even the great poet Edmund Spenser recounted Lear's tragedy in Canto 10, Book II of The Faerie Queen (1590). All of the aforementioned versions of the tale, and possibly dozens more, were readily available to Shakespeare and shaped the main plot of his own drama. However, it is clear that Shakespeare relied chiefly on King Leir, fully titled The True Chronicle History of King Leir, and his three daughters, Gonorill, Ragan, and Cordella, the anonymous play published twelve years before the first recorded performance of Shakespeare's King Lear.

In 1594, entrepreneur and theatre manager Philip Henslowe noted in his diary that King Leir was performed at the Rose Theatre in London as a springtime co-production by the Queen's Men and Lord Sussex's Men, two of the most prominent acting companies of the day. That same year a bookseller named Edward White obtained a license to publish the play, but since no copy of the play printed in that year survives, we do not know if White went through with an actual printing. In May of 1605, another license was obtained to publish King Leir, this time by a printer named Simon Stafford. It is through the efforts of Stafford and his co-publisher, John Wright, that we have a surviving printed edition of the play.

Although King Leir retains the ending found in earlier accounts of the story, in which Cordelia lives and Leir is restored to the throne, the anonymous play incorporates vivid new characters (the most crucial being Perillus) and situations which are not found in any of the previous retellings of the tale, thus expanding the sparse legend into an effective, five-act play.

Shakespeare, in turn, expands on King Leir's original elements. He changes Perillus' name to Kent, and adopts most of the scenes shared between Leir and Perillus. Compare Lear's famous speech 2.4 to the analogous speech found in 3.3 of King Leir:

Lear. O, reason not the need: our basest beggars

Are in the poorest thing superfluous:

Allow not nature more than nature needs,

Man's life's as cheap as beast's: thou art a lady;

If only to go warm were gorgeous,

Why, nature needs not what thou gorgeous wear'st,

Which scarcely keeps thee warm. But, for true need,-

You heavens, give me that patience, patience I need!

You see me here, you gods, a poor old man,

As full of grief as age; wretched in both!

If it be you that stir these daughters' hearts

Against their father, fool me not so much

To bear it tamely; touch me with noble anger,

And let not women's weapons, water-drops,

Stain my man's cheeks!

(King Lear, 2.4.291-305) | Leir. Nay, if thou talk of reason, then be mute;

For with good reason I can thee confute.

If they, which first by nature's sacred law,

Do owe to me the tribute of their lives;

If they to whom I always have been kind,

And bountiful beyond comparison;

If they, for whom I have undone myself,

And brought my age unto this extreme want,

Do now reject, contemn, despise, abhor me,

What reason moveth thee to sorrow for me?

(King Leir, 3.3.79-90)

|

Notice also the similarities in the two plays as the king first confronts his three daughters.

Lear. Know that we have divided

In three our kingdom: and 'tis our fast intent

To shake all cares and business from our age;

Conferring them on younger strengths, while we

Unburthen'd crawl toward death. Our son of Cornwall,

And you, our no less loving son of Albany,

We have this hour a constant will to publish

Our daughters' several dowers, that future strife

May be prevented now. The princes, France and Burgundy,

Great rivals in our youngest daughter's love,

Long in our court have made their amorous sojourn,

And here are to be answer'd. Tell me, my daughters,-

Since now we will divest us both of rule,

Interest of territory, cares of state,-

Which of you shall we say doth love us most?

That we our largest bounty may extend

Where nature doth with merit challenge. Goneril,

Our eldest-born, speak first.

Gon. Sir, I love you more than words can wield the matter;

Dearer than eye-sight, space, and liberty;

Beyond what can be valued, rich or rare;

No less than life, with grace, health, beauty, honour;

As much as child e'er loved, or father found;

A love that makes breath poor, and speech unable;

Beyond all manner of so much I love you.

Cord. {Aside}

Love, and be silent.

Lear. Of all these bounds, even from this line to this,

With shadowy forests and with champains rich'd,

With plenteous rivers and wide-skirted meads,

We make thee lady: to thine and Albany's issue

Be this perpetual. What says our second daughter,

Our dearest Regan, wife to Cornwall? Speak.

Reg. Sir, I am made

Of the self-same metal that my sister is,

And prize me at her worth. In my true heart

I find she names my very deed of love;

Only she comes too short: that I profess

Myself an enemy to all other joys,

Which the most precious square of sense possesses;

And find I am alone felicitate

In your dear highness' love.

Cord. {Aside}

And yet not so; since, I am sure, my love's

More richer than my tongue.

Lear. To thee and thine hereditary ever

Remain this ample third of our fair kingdom;

No less in space, validity, and pleasure,

Than that conferr'd on Goneril. Now, our joy,

Although the last, not least; to whose young love

The vines of France and milk of Burgundy

Strive to be interess'd; what can you say to draw

A third more opulent than your sisters? Speak.

Cord. Nothing, my lord.

Lear. Nothing!

Cord. Nothing.

Lear. Nothing will come of nothing: speak again.

Cord. Unhappy that I am, I cannot heave

My heart into my mouth: I love your majesty

According to my bond; nor more nor less.

(King Lear, 1.1.38-94)

|

Leir. Dear Gonorill, kind Ragan, sweet Cordella,

Ye flourishing branches of a kingly stock,

Sprung from a tree that once did flourish green,

Whose blossoms now are nipped with winter's frost,

And pale grim death doth wait upon my steps,

And summons me unto his next assizes.

Therefore, dear daughters, as ye tender the safety

Of him that was the cause of your first being,

Resolve a doubt which much molests my mind,

Which of you three to me would prove most kind;

Which loves me most, and which at my request

Will soonest yield unto their father's hest.

Gon. I hope, my gracious father makes no doubt

Of any of his daughters' love to him:

Yet for my part, to show my zeal to you,

Which cannot be in windy words rehearsed,

I prize my love to you at such a rate,

I think my life inferior to my love.

Should you enjoin me for to tie a millstone

About my neck, and leap into the sea,

At your command I willingly would do it:

Yea, for to do you good, I would ascend

The highest turret in all Brittany,

And from the top leap headlong to the ground:

Nay, more should you appoint me for to marry

The meanest vassal in the spacious world,

Without reply I would accomplish it:

In brief, command whatever you desire,

And if I fail no favour I require.

Leir. O, how my words revive my dying soul!

Cord. O, how I do abhor this flattery!

Leir. But what saith Ragan to her father's will?

Rag. O, that my simple utterance could suffice,

To tell the true intention of my heart,

Which burns in zeal of duty to your grace,

And never can be quenched, but by desire

To show the same in outward forwardness.

Oh, that there were some other maid that durst

But make a challenge of her love with me;

I would make her soon confess she never loved

Her father half so well as I do you.

Ay then, my deeds should prove in plainer case,

How much my zeal aboundeth to your grace:

But for them all, let this one mean suffice,

To ratify my love before your eyes:

I have right noble suitors to my love,

No worse than kings, and haply I love one:

Yet, would you have me make my choice anew,

I would bridle fancy, and be ruled by you.

Leir. Did never Philomel sing so sweet a note.

Cord. Did never flatterer tell so false a tale.

Leir. Speak now, Cordella, make my joys at full,

And drop down nectar from thy honey lips.

Cord. I cannot paint my duty forth in words

I hope my deeds shall make report for me:

But look what love the child doth owe the father,

The same to you I bear, my gracious lord.

(King Leir, 1.3.28-92)

|

Shakespeare also borrows several smaller yet important details from King Leir:

It was the advice with which the old dramatist [of King Leir] credited Skalliger, whose time-serving propensities helped to generate the wicked servility of Goneril's servant, Oswald. Something of the stage business which is associated in Shakespeare's tragedy with the exchange of letters, e.g. between Regan and Goneril (IV. ii. 82), Kent and Cordelia (IV. iii, seq.), and Goneril and Edmund (IV. v, passim), seems traceable to the interception by Gonoril in the old play of letters addressed to Leir (III. v. 45, seq) and to the passage of letters between Ragan and Gonoril (IV. iii. passim). Ragan's angry outburst of unfilial heartlessness on reading Gonoril's written complaint of the old King's 'presumption' (IV. iii. 14, seq) may have given the cue to the splendid outcry in Shakespeare's piece of filial sympathy to which Cordelia gives passionate utterance on receiving Kent's written report of her father's distresses (IV. iii. 11-34).

(Lee xli)

Faced with incessant comparisons to Shakespeare's profound tragedy, King Leir often is dismissed as a prosaic, didactic failure, worth little study in its own right. However, some feel that the play is not without artistic merit, and, although the quality of poetry cannot match that found in King Lear, it is an entertaining work with lively verse and interesting imagery. I have prepared Act One, Scene One of King Leir online, so that you may judge for yourself.

How to cite this article:

Mabillard, Amanda. The True Chronicle History of King Leir. Shakespeare Online. 20 Aug. 2000. < http://www.shakespeare-online.com/plays/kinglear/kingleir.html >.

_____

Related Articles

King Lear: The Complete Play King Lear: The Complete Play

King Lear Overview King Lear Overview

King Lear: Analysis by Act and Scene King Lear: Analysis by Act and Scene

Aesthetic and Textual Examination Questions on King Lear Aesthetic and Textual Examination Questions on King Lear

Blank Verse in King Lear Blank Verse in King Lear

King Lear Lecture Notes and Study Topics King Lear Lecture Notes and Study Topics

The First Publication of King Lear The First Publication of King Lear

The Fool in King Lear and his Function in the Play The Fool in King Lear and his Function in the Play

The Shakespeare Sisterhood: Cordelia The Shakespeare Sisterhood: Cordelia

The Condition of Lear's Mind The Condition of Lear's Mind

Goneril: Physically, Intellectually, and Morally Goneril: Physically, Intellectually, and Morally

Difficult Passages in King Lear Difficult Passages in King Lear

Scene-by-Scene Questions on King Lear with Answers Scene-by-Scene Questions on King Lear with Answers

King Lear Summary King Lear Summary

King Lear Essay Topics King Lear Essay Topics

King Lear Character Introduction King Lear Character Introduction

Sources for King Lear Sources for King Lear

Representations of Nature in Shakespeare's King Lear Representations of Nature in Shakespeare's King Lear

King Lear: FAQ King Lear: FAQ

Famous Quotations from King Lear Famous Quotations from King Lear

Pronouncing Shakespearean Names Pronouncing Shakespearean Names

Shakespeare's Language Shakespeare's Language

Shakespeare's Metaphors and Similes Shakespeare's Metaphors and Similes

Shakespeare's Reputation in Elizabethan England Shakespeare's Reputation in Elizabethan England

Shakespeare's Impact on Other Writers Shakespeare's Impact on Other Writers

Why Study Shakespeare? Why Study Shakespeare?

What is Tragic Irony? What is Tragic Irony?

Characteristics of Elizabethan Drama Characteristics of Elizabethan Drama

Shakespeare Quotations (by Theme and Play) Shakespeare Quotations (by Theme and Play)

|

|