| directory |

| home | contact |

|

|||||||||||||||

| search | |||||||||||||||

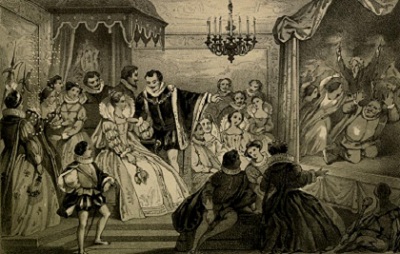

An Elizabethan ChristmasFrom The Elizabethan People by Henry Thew Stephenson. New York: H. Holt & Co.Of all the year no period was looked forward to with an interest like that inspired by the approach of Christmas and the following days. The principal characteristic of the Yule-tide sports was general hospitality and the closely related unbinding of social ties. It was the one time of the year when there was practically no distinction of class, when lord, lady, and rustic met in the same hall, played the same games, and romped without stint as if they were social equals. The proper period for the Yule-tide sports was from Christmas Eve to Twelfth Day; but, especially among the lower classes, this period was extended in both directions. It was customary during this period to decorate the halls, houses, etc., with bay, laurel, ivy, and holly leaves, decorations which were kept in place to the end of the period of celebration. An allusion in Stow's Survey of London to this habit contains also an allusion to the extension of the period of celebration by the common people. "Against the feast of Christmas," he says, "every man's house, as also their parish churches, were decked with holm, ivy, bays, and whatsoever the season of the year afforded to be green. The conduits and the standards in the streets were likewise garnished. Amongst which I read, that in the year 1444, by tempest of thunder and lightning, on the first of February at night, Paul's steeple was fired, but with great labour quenched, and towards the morning of Candlemas day, at the Leadenhall in Comhill, a standard of tree, being set up in the pavement fast in the ground, nailed full of holm and ivy, for disport of Christmas to the people, etc." On Christmas Eve the people were wont to light candles, called Christmas candles, of prodigious size, and to stir the fire till it burned with uncommon brightness. In the midst of this extra illumination the yule-log was brought in. It was the special duty of the household carpenter to provide the Christmas block which was the massive root or trunk of a tree capable of remaining a part of the fire for a number of days. It was brought into the centre of the hall on Christmas eve amid great rejoicing, and, while still there, each member of the household would come forward, seat himself or herself upon it and sing a Yule-song and drink to a merry Christmas and a happy New Year. It was then rolled amid a great tumult to the fire-place and, when properly set up and the material arranged about it for fire, the yule-log was actually ignited by the brand that had been expressively saved for the purpose from last year's Christmas fire. The whole household, including family, friends, and domestics then feasted to a late hour upon Yule-dough, Yule-cakes, and bowls of frumity, with much music and singing. In Roman Catholic times special arrangements were made whereby the poorer people found it easy to collect money by begging, which was to be applied to the purchase of masses for the forgiveness of the excesses to which they went during the Christmas revels. In the time of Shakespeare this custom was still in vogue in the form of carols sung early on Christmas morning especially, as a regular custom, but also carols or songs of a more secular nature that were sung at all times during Yule-tide, with a collection to follow. This custom was frequently followed or accompanied by mumming where a number of persons went about together, from hall to hall, hoping for entertainment and gratuitous remuneration. The dinner upon Christmas day was served with special sumptuousness, with great attention paid to the "dishes for show," as Markham calls them, namely, fancy dishes representing objects, got up with great elaboration, but not meant to be eaten. Not exactly conforming to the latter requirement, however, was the peacock pie, in which the cock was cooked whole, with the head projecting through the crust. The head of the cock would be beautifully decorated at the serving, and the bill gilded; and the tail set up in all its extended grandeur of coloured beauty. Though the following description of a Christmas dinner is from Nichols's accounts of the court, it is not more elaborate than that of many of the noblemen of the court, and differs but little from the celebration of even less wealthy people: "On Christmas day, service in the church being ended, the gentlemen presently repair into the hall to breakfast, with brawn, mustard, and malmsey.In Middleton's Father Hubbard's Tales a number of distinctively Christmas sports are alluded to, among which are carols, wassail bowls, the dancing of Sellinger's Round, Shoeing the Mare, Hoodman Blind, Hot-Cockles, and playing the King and Queen at Twelfth Night. Sellinger's Round, or The Beginning of the World as it was also called, is alluded to in Heywood's The Fair Maid of the West. "I am so tired with dancing with these same black shee chimney sweepers, that I can scarce set the best leg forward, they have so tir'd me with their mariscoes, and I have so tickled them with our country dances. Sellinger's Round, and Tom Tiler: we have so fiddled it." Hoodman Blind is our Blind Man's Buff, and Hot-Cockles is a game still played under various names. One player was blind-folded and the others struck him, he trying to guess who had dealt the blow. Shoe the Mare was another boisterous Christmas sport. "One of the players was chosen to be the wild mare, and the others chased him about the room with the object of shoeing him." (Bullen.) The Lord of Misrule or Abbot of Unreason is familiar to all readers of Sir Walter Scott. Of this personage, who figured, but with less importance, in the rites of Whitsuntide, was one of the most important officers of the Christmas celebration. "In the feast of Christmas," says Stow, "there was in the King's house wheresoever he lodged, a Lord of Misrule, or Master of merry desports, and the like had ye in the house of every nobleman of honour, or good worship, were he spiritual or temporaL Amongst the which, the Mayor of London and either of the Sheriffs had their several Lords of Misrule, ever contending without quarrel or offence, who should make the rarest pastimes to delight the beholders. These lords, beginning their rule on Alhallow Eve, continue the same till the morrow after the feast of the Purification, commonly called Candlemas Day. In which space there was fine and subtle disguisings, masques and mummeries, with playing at cards for counters, nayles and points, in every house, more for pastime than for gain." And Stubbes, in The Anatomy of Abuses, prints the following tirade: "First, all the wilde heads of the parish, flocking together, chuse them a graunde captain (of mischief) whom they inrolle with the title of my Lord of misrule, and him they crown with great solemnities, and adopt for their king. This king annoynted, chooseth forth twentie, fourtie, threescore, or a hundred lustie guttes like to himselfe to wait upon his lordly majesty, and to guarde his noble person .... Thus all things set in order, then have they their hobby-horses, their dragons and other antiques, together with their baudie pipers, and thundering drummers, to strike up the Devils Daunce withall: then march this heathen company towards the church and church-yarde, their pypers pypyng, their drummers thundering, their stumps dauncing, their bells jyngling, their handkerchiefs fluttering about their heads like madmen, their hobby-horses and other monsters skirmishing amongst the throng: and in this sorte they goe to the church like devils incarnate, with such a confused noise, that no man can heare his own voyce. Then the foolish people they looke, they stare, they laugh, they fleere, and mount upon formes and pewes, to see these goodly pagants solemnised in this sort. Then, after this about the church they goe agine and agine, and so foorth into the church yard, where they have commonly their summer haules, their bowers and arbours, and banquetting houses set up, wherein they feast, banquet, and daunce all that day, and (peradventure) all that night too."This description, though it applies to the summer election of the Lord of Misrule, differs from the Christmas celebration only in the out-of-door element. How to cite this article:______ Related Resources |

|

©1999-2021 Shakespeare Online. All Rights Reserved.