| directory |

| home | contact |

|

|||||||||||||||

| search | |||||||||||||||

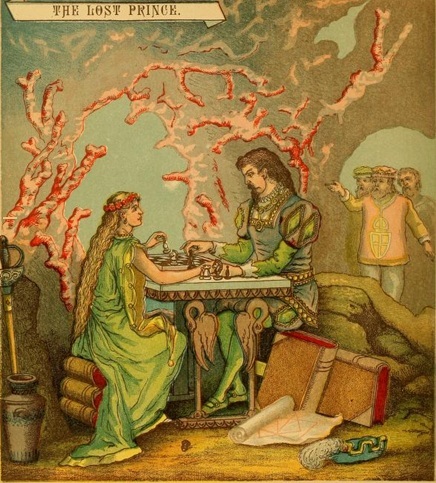

The Relationship Between Miranda and FerdinandFrom Shakespeare's Comedy of The Tempest. Ed. William J. Rolfe. New York: American Book Company. Miranda is a unique and exquisite creation of the poet's magic. She is his ideal maiden, brought up from babyhood in an ideal way — the child of nature, with no other training than she received from a wise and loving father — an ideal father we may say. She reminds me of Wordsworth's lovely picture of the child whom nature has adopted as her own:— "Three years she grew in sun and shower,into her face, and into her soul no less, the spiritual effect of nature's influences being as marked as the physical. And nature on this enchanted island is more than nature anywhere else on earth, for the supernatural — that which is beyond and above nature — is added, through the potent and benign art of Prospero. He has been her teacher too — a loving teacher with ample leisure for the training of this single pupil, the sole companion, comfort, and hope of his exile life. He says:— "Here in this island we arriv'd; and here  An excellent education, the worldly-wise may say, for the maiden on the lonely isle, if she is to live there all her days with her wise and watchful father for sole companion and guardian; but will she not make a fool of herself if she is suddenly removed from this

isolated existence to the ordinary surroundings of her sex? How will this child of nature behave in the artificial world of "society?" We may trust Shakespeare to solve this problem successfully, but

who else than he could have done it? Who else would have dared to bring this innocent and ignorant creature — ignorant at least of all the conventional ways of social life — face to face with a lover,

and that lover a prince, the flower of courtly cultivation and gallantry, as her very first experience of the new world to which she is destined to be transferred? The result is one of the highest triumphs of his art, — because, as he himself has said in referring to the development of new beauty in flowers by cultivation, "the art itself is nature" (Winter's Tale, iv. 4. 97). This modest wildflower, under his fostering care, unfolds into a blossom of rarer beauty, fit for a king's garden, without losing anything of its native delicacy or sweetness. As Mrs. Jameson says, "There is nothing of the kind in poetry equal to the scene between Ferdinand and

Miranda." To attempt to comment upon it would be to gild refined gold or to paint the lily; and I shall be guilty of no such "wasteful and ridiculous excess."

An excellent education, the worldly-wise may say, for the maiden on the lonely isle, if she is to live there all her days with her wise and watchful father for sole companion and guardian; but will she not make a fool of herself if she is suddenly removed from this

isolated existence to the ordinary surroundings of her sex? How will this child of nature behave in the artificial world of "society?" We may trust Shakespeare to solve this problem successfully, but

who else than he could have done it? Who else would have dared to bring this innocent and ignorant creature — ignorant at least of all the conventional ways of social life — face to face with a lover,

and that lover a prince, the flower of courtly cultivation and gallantry, as her very first experience of the new world to which she is destined to be transferred? The result is one of the highest triumphs of his art, — because, as he himself has said in referring to the development of new beauty in flowers by cultivation, "the art itself is nature" (Winter's Tale, iv. 4. 97). This modest wildflower, under his fostering care, unfolds into a blossom of rarer beauty, fit for a king's garden, without losing anything of its native delicacy or sweetness. As Mrs. Jameson says, "There is nothing of the kind in poetry equal to the scene between Ferdinand and

Miranda." To attempt to comment upon it would be to gild refined gold or to paint the lily; and I shall be guilty of no such "wasteful and ridiculous excess."

I may, however, venture to call attention to the unconscious humour of Miranda's reply to her father, when, in playing the part of pretended distrust of Ferdinand, he says:— "foolish wench!"My affections," she replies, — "Are then most humble; I have no ambitionOther men may be angels, in comparison with Ferdinand, but he is good enough for her. And again must "inward laughter" have "tickled all his soul" (to borrow Tennyson's phrase) when Ferdinand is piling the logs, and the sympathetic girl comes to cheer him, little suspecting that Prospero is hidden within earshot. Love has made the artless maiden artful, and she suggests that the young man may shirk the unprincely labour for the nonce:— "My fatherPretty traitor to the one authority that has been the law of her life till now! Miranda's frank offer to carry logs while Ferdinand rests is a natural touch that might at first seem unnatural, but how thoroughly in keeping with the character it is after all. This child of nature, healthy, strong, active, familiar with the rough demands of life on this uninhabited island, and unfamiliar with the chivalrous deference to woman that exempts her from menial labour in civilized society, sees nothing "mean" or "odious" or "heavy" in piling the wood, as Ferdinand does; and when he resents the idea of her undergoing such "dishonour" while he sits lazy by, nothing could be more natural than her reply:— "It would become meIt is hard for him every way — as severe a strain upon his muscles as upon his pride. As he says later:— "I am, in my condition,Ferdinand has been well characterized by Miss O'Brien, in her paper on Shakespeare's Young Men, in the Westminster Review. In her classification of these youths she puts Ferdinand and Florizel (of The Winter's Tale) together: "They are as much alike in nature as their charming companions, Miranda and Perdita. Both are wonderfully fresh and natural for the products of court training; both fall in love swiftly and completely; both have that tender grace, that purity of affection, shown in many others, but never more perfectly than in them. Theirs is not the wild passion of Romeo and Juliet; there is nothing high-wrought and feverish about their love-making; it is the simple outcome of pure and healthy feeling; and it is difficult to say which gives us the prettier picture — Ferdinand holding Miranda's little hands on the lonely shore, or Florizel receiving Perdita's flowers among the bustle of the harvesting. Ferdinand has the most fire and energy, though he should not have been the first to desert the ship in the magic storm. He has the best character altogether, showing much affection for his father, and a manly, straightforward way of going to work generally. Florizel is grace and charm personified, and has the most bewitching tongue; but he is too pliant, too taken up with one idea, to be quite so satisfactory." As to Ferdinand's behaviour in the shipwreck, it was due to the fact that it was a "magic storm" and he was not his own master. It was a part of Prospero's plan that the people on board the ship should be scattered in certain groups on shore and that Ferdinand should be separated from the rest; and Ariel carries out his master's directions. When Prospero afterward asks him whether the men are all safe, he replies:— "Not a hair perish'd;

How to cite this article:_________

Related Articles

|

©1999-2021 Shakespeare Online. All Rights Reserved.