| directory |

| home | contact |

|

|||||||||||||||

| search | |||||||||||||||

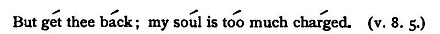

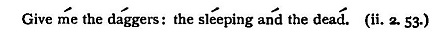

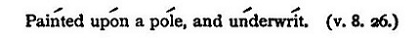

The Metre of MacbethFrom Macbeth. Ed. Thomas Marc Parrott. New York: American Book Co.In order to enjoy to the full the poetry of such a play as Macbeth the student should be able to read it rhythmically, and to do this demands some knowledge, at least, of the general principles of Shakespearean versification. The metre of Macbeth is, as is well known, very irregular. This is due, perhaps, in some few places to the corrupt state of the text, but more generally to the fact that by the time he wrote Macbeth Shakespeare had acquired such a mastery of language and metre that he often disregarded the rules which earlier poets, and he himself in his earlier works, had carefully observed. One often feels in reading Macbeth that Shakespeare did not compose the drama line by line, but rather in groups of lines, and that so long as each group produced the rhythmical effect he sought, it mattered little to him whether or not the individual lines conformed to strict metrical rule. At the same time it is necessary for us to know these rules, if only to appreciate the freedom with which Shakespeare departs from them. The simplest division of the drama is into prose and verse. There is comparatively little prose in Macbeth, The letter in i. 5 is naturally in prose; the porter in ii. 3 talks prose as do most of Shakespeare's low comedy characters; the dialogue between Lady Macduff and her son in iv. 2 wavers between verse and prose in a rather curious fashion (see note on this passage, page 260); and finally the sleep-walking scene, v. i, is for the most part in prose. This may be explained by the fact that Shakespeare almost without exception puts prose rather than verse into the mouths of the insane, and Lady Macbeth's somnambulism is meant by him to be regarded as a symptom of her mental disorder. The verse of the drama falls naturally into two parts: (a) blank verse, that is, unrhymed lines in iambic pentameter; (b) rhymed lines in various metres. Blank verse — The normal blank verse line is an iambic pentameter, that is, it contains five feet of two syllables each, the second of which is accented; or, to use a more modern terminology, it is a sequence of ten alternately unstressed and stressed syllables. We may denote this line most simply by placing an accent over each stressed syllable, as,

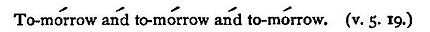

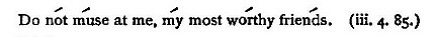

To point out the stresses of a line in this way corresponds in the study of English metre to the elaborate system of scanning classical verse which has sometimes been applied to English poetry. It is evident that a prolonged succession of such regular lines would be extremely monotonous. This may easily be seen by reading aloud some of the longer passages in Shakespeare's earlier plays, such as the Comedy of Errors, where many of these regular lines occur in unbroken succession. In order to avoid such monotony Shakespeare soon began to make use of a number of variations from the normal line. Some of these from their frequent occurrence in Macbeth deserve particular notice. Instead of ending with a stressed syllable Shakespeare frequently added an unstressed syllable to the line. This so-called feminine ending, appears in something over a quarter of the blank verse lines of Macbeth:

Sometimes two such syllables are added, making what is called the triple, or the double feminine, ending.

The Alexandrine or line of six feet resembles the line with the double feminine ending in having twelve syllables, but differs from it in closing with a stressed syllable. Thus:

Sometimes an Alexandrine takes on an extra unstressed syllable at the close. Thus:

Akin to the feminine ending is the addition of an unstressed syllable to the foot preceding the caesura, i.e. the pause in the middle of the line. Thus:

Occasionally two unstressed syllables are added here. Thus:

On the other hand Shakespeare often dropped an unstressed syllable from the line. Thus:

Occasionally a stressed syllable is omitted giving us a line of four feet:

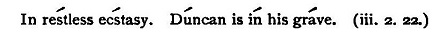

We find also lines in which one or more feet are entirely omitted. Thus:

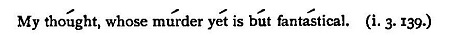

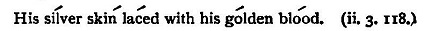

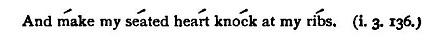

Of these fragmentary lines it may be remarked that lines of two and three feet are by no means uncommon, twenty-nine of the first class, and fifty-one of the second, occurring in Macbeth. Lines of four feet are rarer, and lines of one foot rarest of all. Another method of varying the normal line is the substitution of some other foot for the iamb in one or more places of the line. The commonest substitution is that of the trochee, i.e. a, foot of two syllables with the stress on the first. This substitution is sometimes called "stress-inversion." As a rule it appears in the first foot or after the caesura; but it may occur in any foot of the line. Thus we have it in the first foot,

in the second,

in the third,

in the fourth,

in the fifth,

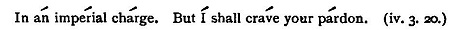

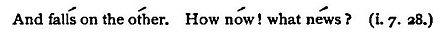

Occasionally we find two and very rarely three such inversions in one line. Sometimes an anapaest, i.e. a foot consisting of two unstressed and one stressed syllable, is substituted for an iamb. This substitution is often more apparent than real, for many such cases can be explained by the contraction of words common in Shakespeare's day; but there are some cases where contraction is impossible. Thus we have.

and

In scanning, attention must, of course, be paid to differences of pronunciation between the English of Shakespeare's time and our own. Some of the more striking of these have been pointed out in the notes. Attention must also be paid to the frequent contraction of two words or two syllables into one. Such contractions as "I'll" for "I will," "I've " for "I have" are sometimes indicated in the text, but frequently are left to the judgment of the reader. An unaccented syllable in the middle of a word is often slurred over in scanning; thus in such a line as

the second syllables of "corporal" and "terrible" are barely heard, if at all. On the other hand there are a few cases where one syllable is expanded into two for the sake of the metre. Thus in the line

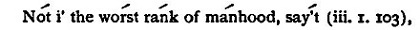

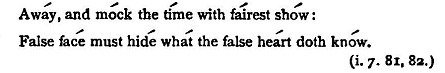

"worst" is practically equivalent to "worest." The same word is sometimes pronounced differently in different places according to the requirement of the meter. Thus the termination "-ion" is pronounced as two syllables in i. 2. 18, but is contracted to one in i. 4. I. Compare also the pronunciations of "remembrance" in ii. 3. 67 and iii. 2. 30. No rule can be given for such cases; the reader's ear for rhythm must serve as his guide. We must not forget that Shakespeare wrote his verse to be declaimed from the boards of a theatre, not to be puzzled over in a schoolroom. Many lines that tax the ingenuity of scholars who attempt to fit them into an exact metrical scheme, would flow smoothly enough when spoken by a good actor. Rhymed Lines — The rhymed lines in Macbeth may be divided into (1) Heroic couplets. i.e. iambic pentameter lines, each pair of lines rhyming as

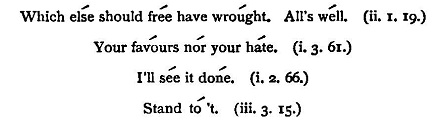

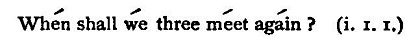

Such couplets frequently occur at the end of a scene, where they are called rhymed "tags." Out of twenty-eight scenes in Macbeth nineteen end with a "tag" of this kind. Heroic couplets, however, appear occasionally in the middle of a scene in blank verse. See lines 90-101 of iv. i. There are some fifty-four such couplets in Macbeth. (2) Lyrical passages. The ordinary dialogue of the witches, as has been pointed out in the notes is thrown into rhymed verse, consisting for the most part of trochaic tetrameter, i,e. lines of four feet, having two syllables to a foot, with the stress falling on the first. Thus:

As a rule the second syllable of the last foot is wanting in this metre; but see i. 3. 14. Occasionally we find iambic lines in the speeches of the witches as

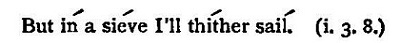

In the speeches of Hecate on the other hand (see iii. 5. and iv. i.) the rhythm is iambic. There is occasional stress inversion but not a single trochaic line. This is one of several arguments against the Shakespearean authorship of these passages. The same argument would hold against the speech of the First Witch iv. i. 125- 132. Here and there in the witches' speeches we have lines that exceed the regular number of feet as

or fall short of it as

There are about 120 short rhyming lines in the whole play. How to cite this article: ______________ More Resources |

More to Explore |

©1999-2021 Shakespeare Online. All Rights Reserved.