| directory |

| home | contact |

|

|||||||||||||||

| search | |||||||||||||||

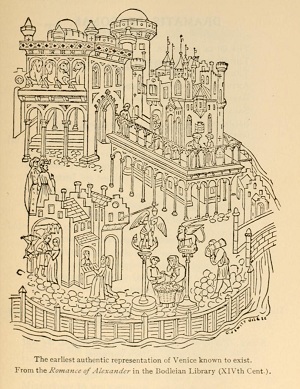

Setting, Atmosphere and the Unsympathetic Venetians in The Merchant of VeniceFrom Notes on Shakespeare's Workmanship by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch. New York: Henry Holt and Company.Since in the end it taught me a good deal, and since the reader too may find it serviceable, let me start by shortly rehearsing my own experience with The Merchant of Venice. I came first to it as a schoolboy, and though I got it by heart I could not love the play. I came to it (as I remember) straight from the woodland enchantments of As You Like It, and somehow this was not at all as I liked it. No fairly imaginative youngster could miss seeing that it was picturesque or, on the face of it, romantic enough for any one: as on the face of it no adventure should have been more delightful than to come out of the green Forest of Arden into sudden view of Venice, spread in the wide sunshine, with all Vanity Fair, all the Carnival de Venise, in full swing on her quays; severe merchants trafficking, porters sweating with bales, pitcher-bearers, flower-girls, gallants; vessels lading, discharging, repairing; and up the narrower waterways black gondolas shooting under high guarded windows, any gondola you please hooding a secret - of love, or assassination, or both - as any shutter in the line may open demurely, discreetly, giving just room enough, just time enough, for a hand to drop a rose; Venice again at night - lanterns on the water, masqued revellerss taking charge of the quays with drums, hautboys, fifes, and general tipsiness; withdrawn from this riot into deep intricacies of shadow, the undertone of lutes complaining their love; and out beyond all this fever, far to southward, the stars swinging, keeping their circle - as Queen Elizabeth once danced - "high and disposedly" over Belmont, where on a turfed bank - Peace ho! the moon sleeps with Endymion,though the birds have already started to twitter in Portia's garden. Have we not here the very atmosphere of romance? Well, no, ... We have a perfect setting for romance; but setting and atmosphere are two very different things. I fear we all suffer temptation in later life to sophisticate the thoughts we had as children, often to make thoughts of them when they were scarcely thoughts at all. But fetching back as honestly as I can to the child's mind, I seem to see that he found the whole thing heartless, or (to be more accurate) that he failed to find any heart in it and was chilled: not understanding quite what he missed, but chilled, disappointed none the less. Barring the Merchant himself, a merely static figure, and Shylock, who is meant to be cruel, every one of the Venetian dramatis personae is either a 'waster' or a 'rotter' or both, and cold-hearted at that. There is no need to expend ink upon such parasites as surround Antonio - upon Salarino and Salanio. Be it granted that in the hour of his extremity they have no means to save him. Yet they see it coming; they discuss it sympathetically, but always on the assumption that it is his affair - Let good Antonio look he keep his day.and they take not so much trouble as to send Bassanio word of his friend's plight, though they know that for Bassanio's sake his deadly peril has been incurred! It is left to Antonio himself to tell the news in that very noble letter of farewell and release: Sweet Bassanio: My ships have all miscarried, my creditors grow cruel, my estate is very low, my bond to the Jew is forfeit; and since in paying it it is impossible I should live, all debts are cleared between you and I, if I might but see you at my death. Notwithstanding, use your pleasure: if your love do not persuade you to come, let not my letter.- letter which, in good truth, Bassanio dooes not too extravagantly describe as "a few of the unpleasant'st words that ever blotted paper." Let us compare it with Salarino's account of how the friends had parted: I saw Bassanio and Antonio part:But let us consider this conquering hero, Bassanio. When we first meet him he is in debt, a condition on which - having to confess it because he wants to borrow more money - he expends some very choice diction. 'Tis not unknown to you, Antonio,(No, it certainly was not!) How much I have disabled mine estate That may be a mighty fine way of saying that you have chosen to live beyond your income; but, Shakespeare or no Shakespeare, if Shakespeare mean us to hold Bassanio for an honest fellow, it is mighty poor poetry. For poetry, like honest men, looks things in the face, and does not ransack its wardrobe to clothe what is naturally unpoetical. Bassanio, to do him justice, is not trying to wheedle Antonio by this sort of talk; he knows his friend too deeply for that. But he is deceiving himself, or rather is reproducing some of the trash with which he has already deceived himself. He goes on to say that he is not repining; his chief anxiety is to pay everybody, and To you, Antonio,and thereupon counts on more love to extract more money, starting (and upon an experienced man of business, be it observed) with some windy nonsense about shooting a second arrow after a lost one. You know me well; and herein spend but timesays Antonio; and, indeed, his gentle impatience throughout this scene is well worth noting. He is friend enough already to give all; but to be preached at, and on a subject - money - of which he has forgotten, or chooses to forget, ten times more than Bassanio will ever learn, is a little beyond bearing. And what is Bassanio's project? To borrow three thousand ducats to equip himself to go off and hunt an heiress in Belmont! He has seen her; she is fair; and Sometimes from her eyesNow this is bad workmanship and dishonouring to Bassanio. It suggests the obvious question, Why should he build anything on Portia's encouraging glances, as why should he "questionless be fortunate" seeing that - as he knows perfectly well, but does not choose to confide to the friend whose money he is borrowing - Portia's glances, encouraging or not, are nothing to the purpose, since all depends on his choosing the right one of three caskets - a two to one chance against him? But he gets the money, of course, equips himself lavishly, arrives at Belmont; and here comes in worse workmanship. For I suppose that, while character weighs in drama, if one thing be more certain than another it is that a predatory young gentleman such as Bassanio would not have chosen the leaden casket. I do not know how his soliloquy while choosing affects the reader: The world is still deceived with ornament.- but I feel moved to interrupt: "Yes, yess - and what about yourself, my little fellow? What has altered you, that you, of all men, start talking as though you addressed a Young Men's Christian Association?" And this flaw in characterization goes right down through the workmanship of the play. For the evil opposed against these curious Christians is specific; it is Cruelty; and, yet again specifically, the peculiar cruelty of a Jew. To this cruelty an artist at the top of his art would surely have opposed mansuetude, clemency, charity, and, specifically, Christian charity. Shakespeare misses more than half the point when he makes the intended victims, as a class and by habit, just as heartless as Shylock without any of Shylock's passionate excuse. It is all very well for Portia to strike an attitude and tell the court and the world that The quality of mercy is not strain'd:But these high-professing words are words and no more to us, who find that, when it comes to her turn and the court's turn, Shylock gets but the "mercy" of being allowed (1) to pay half his estate in fine, (2) to settle the other half on the gentlemanand (3) to turn Christian. (Being such Christians as the whole gang were, they might have spared him that ignominy.) Moreover, with such an issue set out squarely in open court, I do not think that any of us can be satisfied with Portia's victory, won by legal quibbles as fantastic as anything in Alice in Wonderland; since, after all, prosecution and defence have both been presented to us as in deadly earnest. And I have before now let fancy play on the learned Bellario's emotions when report reached him of what his impulsive niece had done with the notes and the garments he had lent to her. Indeed, a learned Doctor of another University than Padua scornfully summed up this famous scene to me, the other day, as a set-to between a Jew and a Suffragette. Why are these Venetians so empty-hearted? I should like to believe - and the reader may believe it if he will - that Shakespeare was purposely making his Venice a picture of the hard, shallow side of the Renaissance, even as in Richard III he gives us a stiff conventional portrait of a Renaissance scoundrel ("I am determined to be a villain"), of the Italianate Englishman who was proverbially a devil incarnate. He certainly knew all about it; and in that other Venetian play, Othello, he gives us a real tragedy of two passionate, honest hearts entrapped in that same milieu of cold, practised, subtle malignity. I should like to believe, further, that against this Venice he consciously and deliberately opposed Belmont (the Hill Beautiful) as the residence of that better part of the Renaissance, its 'humanities,' its adoration of beauty, its wistful dream of a golden age. It is, at any rate, observable in the play that - whether under the spell of Portia or from some other cause - nobody arrives at Belmont who is not instantly and marvellously the better for it; and this is no less true of Bassanio than of Lorenzo and Jessica and Gratiano. All the suitors, be it remarked - Morocco and Aragon no less than Bassanio - address themselves nobly to the trial and take their fate nobly. If this be what Shakespeare meant by Belmont, we can read a great deal into Portia's first words to Nerissa in Act V as, reaching home again, she emerges on the edge of the dark shrubbery - That light we see is burning in my hall.- a naughty world: a world that is naught, having no heart. It were pleasant (I say) to suppose this naughtiness, this moral emptiness of Venice; deliberately intended. But another consideration comes in. How to cite this article:______ Related Articles |

|

©1999-2021 Shakespeare Online. All Rights Reserved.