| directory |

| home | contact |

|

|||||||||||||||

| search | |||||||||||||||

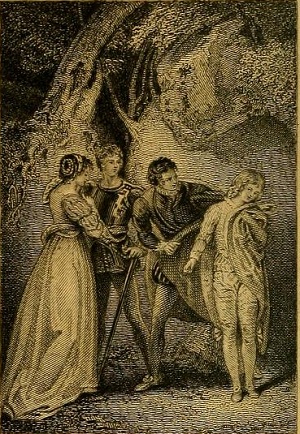

The Two Gentlemen of Verona - Early Experimentation in PlottingFrom The Development of Shakespeare as a Dramatist by George Pierce Baker. New York: Macmillan.In The Two Gentlemen of Verona, first printed in the folio of 1623, but mentioned by Meres in his Palladis Tamia in 1598, we have a play evidently written for the public stage. It is placed by the critics at various dates between 1591 and 1595, with a preference for 1591-1593. What makes it likely that The Two Gentlemen of Verona is, in date of composition, closely related to Love's Labour's Lost, is that in it, too, the love story is both the chief interest and the thread which binds all the incidents together, and that, as we shall see in a moment, its advance beyond Love's Labour's Lost in technique is not great. The slight advance, however, and the decrease in the tendency to quibble and to overemphasize speech at the expense of action show that The Two Gentlemen of Verona followed Love's Labour's Lost. The Two Gentlemen of Verona is indebted to the story of Felismena as told in the Diana Enamorada of Jorge de Montemayor. This book was not printed in English till 1598, but an English manuscript was in circulation from 1582. Possibly, too, Shakespeare knew and used a play acted before the Queen in 1584 entitled Felix and Philiomena. In the Diana Felismena is a maiden destined by Venus and Minerva to be unfortunate in love, but successful in war. She was wooed by a neighbor, Don Felix, and gave him her love after much affected scorn. His father discovered their love and sent Felix to Court to prevent the match. Thither Felismena followed him disguised as a page. On her first night in the city and before she has sought Felix out, she hears him passionately serenading some Court lady in the same street in which she lodges, and learns from her hostess that he is openly paying his addresses to this lady. Next day she sees him at Court, a splendid figure in white and yellow, the colors of the lady Celia. Felismena maintains her disguise as the page Valerius, enters the service of Felix in order to be near him, and carries his tokens and messages to Celia with earnest pleadings of her own for the happiness of her false iover. Celia, still cold to Felix, waxes warm to Valerius, and when she cannot move him dies of unrequited love. Then Felix disappears and people suppose him dead of grief. Felismena in despair becomes a shepherdess. After a time she chances upon a knight in the forest, hard pressed by three foes. She delivers him by her skill in archery and discovers that he is Don Felix. His old love for her returns, and she forgives the past. This outline of the original story shows that when Shakespeare wrote The Two Gentlemen of Verona he had waked to a fact constantly demonstrated by his later plays, namely, that the Elizabethan audience of the public theatres liked a crowded and complicated story. To meet this desire, Shakespeare provides not only the figures of the purely comic scenes, but also Valentine, Thurio, and Eglamour. Taking a hint from a portion of the story which he discards, he adds the outlaw scenes. But though he provides more material for his proposed plot, his whole treatment of it proves that he is yet at the beginning of the acquirement of his technique. He feels strongly now the value of contrast in drama, and therefore frankly opposes Valentine to Proteus, Silvia to Julia, as characters, and alternates his scenes of pure exposition or of emotion with scenes of comedy. Sometimes he even splits a scene midway, as in the first scene of Act I, to get this sort of contrast. He has discerned one of the permanent essentials of dramatic composition, contrast, but as yet his art is not sufficient to conceal his methods. It is, however, in his exposition and plotting that he is weakest. It takes this dramatist, who by 1596 at latest has gained a wonderful combination of swiftness and clearness in opening his plays, [See the opening scene of Romeo and Juliet] two acts, including some ten scenes, to state the relations of Proteus, Valentine, Silvia, and Julia; to bring the first three together at the Court; to prepare us for the coming of the fourth; and to introduce us to Launce and Speed. He would have done all this in at most three scenes a few years later: one, as now, showing the planning of Julia with Lucetta to leave Verona and go to the Court in search of Proteus; one preceding scene for Launce and Speed; and a longer scene, now Scene 4 of Act II, in Milan at the Duke's palace, where the coming of Proteus to the Court would bring out clearly his previous relations with Valentine and Julia, the love of Valentine for Silvia, the sudden infatuation of Proteus for her, and the place of Thurio in the story. The movement in these two acts is still closely akin to the slow movement of Love's Labour's Lost. From the beginning of Act III the play moves with constantly increasing suspense for the spectator, but the use of this suspense proves that Shakespeare could not yet handle it perfectly. In Act III, Scene 1, Proteus basely betrays to the Duke the secret of Valentine's love for Silvia. There follow the dramatic banishment of Valentine by the Duke, the perfidy of Proteus as he counsels Valentine to flee, and the amusing dialogue of Speed and Launce. Act III, then, contains at least one good dramatic situation, moves with relative swiftness, and shows especially well the sharp contrasting of serious and comic which Shakespeare delighted in at this time. Moreover, it urges us on to the other acts in order that we may know the outcome of the complications for Valentine and of the perfidy of Proteus. The second scene of this act shows us more perfidy on the part of Proteus when, agreeing to be false to Valentine, he seems to favor Sir Thurio's plan in regard to Silvia, but really schemes only for his own ends. It is, however, a transitional scene preparing us for complications to follow. In the fourth act the first scene simply shows us the taking of Valentine by the outlaws and their choice of him as captain. Scene 2 is probably the most human and charming of the play. It is the serenade of Silvia by Thurio, Proteus, and the musicians which the love-lorn Julia watches from her hiding-place. Even it, however, points forward to scenes seemingly sure to result because Julia now knows that Proteus is false to her. Scene 3, again transitional, shows us Silvia arranging with Eglamour to aid her escape from Milan in search of Valentine. Scene 4, after the opening between Launce and his dog, gives us the second strongly human scene of the play in the talk between Proteus and Julia, still disguised as a page, and her charming interview with Silvia, the latter a kind of preliminary sketch for the scene of Viola and Olivia in Twelfth Night. Yet this complication of the relations of Silvia, Julia, and Proteus reaches no settlement in the act and we turn to the fifth, sure that there, in a series of dramatic scenes or in one long scene, the very complicated relations of the four young people will be worked out. Scene 1, merely transitional, only shows us Eglamour and Silvia leaving Milan. In Scene 2 the Duke, discovering the flight, starts with Proteus and Thurio in pursuit. The very brief third scene shows the capture of Silvia by the outlaws. Now but one scene is left in which to unravel all the complications and satisfy at last our long suspense. Could there be a more complete confession of dramatic ineptitude than that last scene? It fails to do everything for which we have been looking. Valentine, after communing with himself in a way that foreshadows the banished Duke in As You Like It, withdraws as he sees strangers coming through the forest. Proteus, who is accompanied by the faithful Julia, still disguised as a page, has found Silvia and is trying to force his love upon her. Valentine, overhearing, bursts forth and denounces his friend. If Shakespeare did not wish to "hold" the scene of the avowal of his love by Proteus through letting Julia take some part in it, or by prolonging the play of emotion between Proteus and Silvia, he had, on the reappearance of Valentine, an opportunity for a strong scene in which the play and interplay of the feelings of the four characters might lead at last to a happy solution. Yet this is his weak handling of the situation : - Valentine. Now I dare not sayIt is hard enough to believe that Valentine would forgive so promptly, but that he would go as far as to offer to yield up Silvia is preposterous. That touch came simply to motivate the sudden swooning of Julia at the news. Only a little less absurd is the sudden swerve into rightmindedness of Proteus when Julia has revealed herself. After all these startling surprises, however, perhaps one is ready to agree to Julia's glad acceptance of the changeable affections of so worthless a person as Proteus. Is it not clear that in this scene the momentary effect, the start of surprise, mean far more to the dramatist than truth to life and probability? Having lured his audience on by writing scenes which constantly promised complicated action ahead, when the closing in of the afternoon at last drives him to bay, he gets out of his difficulties in the swiftest possible fashion, but with complete sacrifice of good dramatic art, the rich possibilities of his material, and truth to life. Here, then, is a play which shows in Julia and Launce, and in Scenes 2 and 4 of Act IV, that Shakespeare can now do far more in characterization than he had in Love's Labour's Lost. In it, too, his medium of expression is gradually changing its mannered literary quality for genuine dramatic effectiveness. Yet the same play proves that, though he now recognizes the value of complicated plot and of creating suspense in the minds of his hearers, he can neither proportion nor develop firmly the story he has complicated nor properly satisfy the suspense which he has created. Does not the young Shakespeare's omission of Celia's fatal love for the disguised Felismena suggest that, feeling sure comedy must end pleasantly, he did not as yet see how to keep the amusing complication without letting it strike far too serious a note and end fatally? A few years later, in Twelfth Night, Shakespeare finds in just this complication not only the cause for much amusement, but much poetry, and a delicate contrast of grave and gay. In The Two Gentlemen of Verona, as in Love's Labour's Lost, Shakespeare passes swiftly over the graver suggestions of his story. As yet he did not know how to throw his comedy into the finest relief by letting the serious cast slight shadows here and there. Does not this comparison of his accomplishment in these two plays with what he had done in Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece demonstrate that his superiority at first was poetic and literary rather than dramatic; and that the distinction between dramatic ability, in the sense of projecting character by means of dialogue, and theatrical ability, the power of deriving for a special audience from particular material the largest amount of emotional result, was an art which must be learned even in Shakespeare's day? How to cite this article:____ Related Resources |

|

©1999-2021 Shakespeare Online. All Rights Reserved.