Physiognomy and Portraits of Shakespeare

From Shakespeare the Player by Alexander Cargill. London: Constable and Company Ltd.

Beyond what mere tradition has to say on the subject, and omitting at present certain supposed personal references to himself in the Sonnets, there is nothing (excepting, of course, the portraits and only what these suggest) to throw any light on the interesting

question as to what manner of man Shakespeare was in the physiological sense. Was he a tall or medium-sized or small man? Was he physically robust or otherwise? Was his complexion dark or fair? In short, what were the chief physical characteristics which differentiated him

from ordinary men of flesh and blood? The subject is of much interest could facts regarding it be obtained.

...Shakespeare was not only a phenomenon in point of intellectual genius, but he must also have been superbly gifted in the matter of physique. And in this twofold consideration, where can we find his equal in the records of human history? In Leonardo da Vinci, perhaps.

Too little regard has been paid to this aspect of the life and work of Shakespeare; and one has only to consider for a moment, in connection with the absurd heresy as to the authorship of the plays, to find how futile is the endeavour to assign that authorship to a man built physically and temperamentally on such lines as was Bacon.

The writing of the plays (of William Shakespeare) was a sheer physical impossibility to Francis Bacon. Let us, then, consider the portraits with a view to arriving at some reasonable conclusion with regard to the main features of the physiognomy of Shakespeare. And to this end I shall only examine the two authentic portraits of the

dramatist, viz., 'the Bust' and the 'Droeshout' likeness prefixed to the First Folio edition of his works. I should have liked to include the 'Stratford likeness, the 'Jansen'

portrait and the 'Felton Head' also, as they suggest so much that is akin to my own individual leanings with regard to the matter of Shakespeare's physiognomy, but I must

omit any details regarding them, as they can only be considered as more or less doubtful if not ideal portraits. They are therefore referred to as belonging to the latter category.

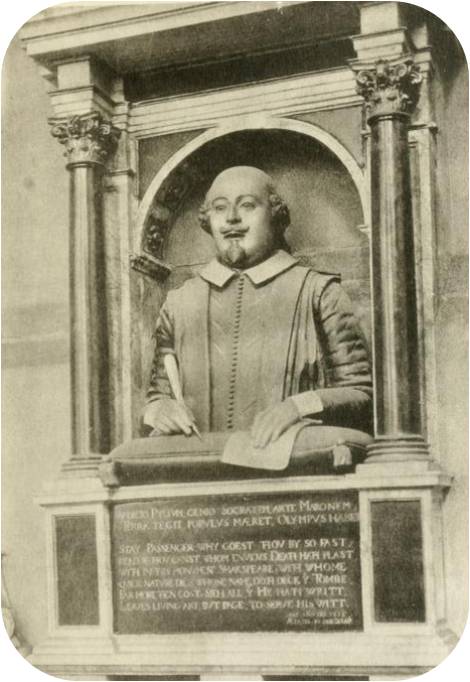

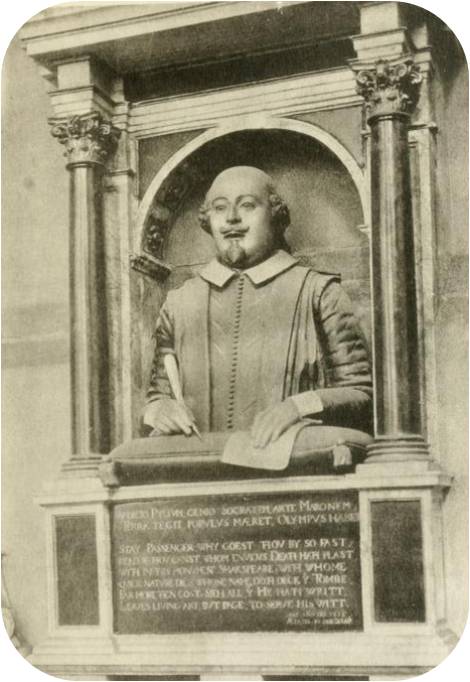

The Bust of Shakespeare

As all the world knows, this is erected in the chancel of the Church of Holy Trinity in his native town of Stratford-on-Avon. With this likeness generations of pilgrims to

that classic shrine have been familiar, ever delighted to gaze upon the marble image with profound admiration.

It is believed that when Shakespeare died, on the 23rd April 1616 (o.s.), exactly fifty-two years of age, a cast of his features was taken— by whom is not known, though the

name of the sculptor of the bust, Gerard or Gerald Johnson, a Hollander, has been suggested. Johnson has been credited with having done his part of the work well, since, before its

erection in the chancel of the church, the bust was probably approved by Shakespeare's relations as a good likeness, and deemed worthy of its conspicuous position and of the man

it represented. As is well known to all who have seen the bust, its prominent characteristic is the calm serenity and gentleness of the expression of the features, an expression

that fairly well satisfies the popular ideal of England's

greatest poet. It is believed that when Shakespeare died, on the 23rd April 1616 (o.s.), exactly fifty-two years of age, a cast of his features was taken— by whom is not known, though the

name of the sculptor of the bust, Gerard or Gerald Johnson, a Hollander, has been suggested. Johnson has been credited with having done his part of the work well, since, before its

erection in the chancel of the church, the bust was probably approved by Shakespeare's relations as a good likeness, and deemed worthy of its conspicuous position and of the man

it represented. As is well known to all who have seen the bust, its prominent characteristic is the calm serenity and gentleness of the expression of the features, an expression

that fairly well satisfies the popular ideal of England's

greatest poet.

Since its erection in the chancel — some time between 1616 and 1623 — the bust has experienced not a few vicissitudes. Originally coloured over to resemble life, a custom of the period, the bust was never once restored or touched up

in any way till 1748 — a century and a quarter afterwards —

when its condition after such a lapse of time can be readily imagined. In the latter year, however, at the instance of an ancestor of the famous actress, Mrs. Siddons, it received

careful and loving attention; the old colours were fetched forth anew, and the monumental setting was improved and made worthy of the poet. The necessary expenses of this

work were, it is interesting to note, defrayed out of the

profits of a representation of the play of Othello by a company of actors 'strolling' by Stratford-on-Avon at the time.

Nearly fifty years after, Mr. Malone, well known in his day as an enthusiastic admirer and commentator of Shakespeare, bethought him that the bust required further

renewing, and took it upon himself to 'cover it over with one or more coats of white paint, thus,' in the opinion of those who witnessed the sacrilegious act, 'at once destroying its

original character and greatly injuring the expression of the face.' For this unfortunate display of hero-worship Malone was severely censured, and there is at least one record extant

that expresses in a measure the feeling of annoyance his action created at the time. In the old visitors' album at the Church of Holy Trinity the following lines were inscribed

as a protest against Malone's offence :

Stranger, to whom this monument is shewn,

Invoke the poet's curse upon Malone;

Whose meddling zeal his barbarous taste betrays,

And daubs his tombstone, as he mars his plays!'

The bust remained for many years in the condition in which Malone had left it. Eventually, however, it was restored once more. Malone's daub was completely obliterated, and the original colouring, as 'improved' in the year 1748, as far as possible renewed. In that satisfactory condition the bust has, with careful tending, remained ever

since, though it has been occasionally touched up to preserve the glorious features of the carved marble as they deserve to be, and doubtless will be, preserved in all time

to come.

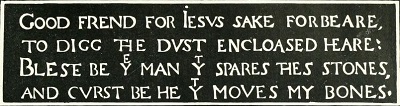

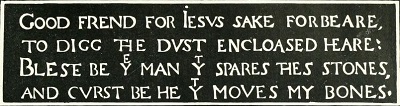

The inscriptions on the mural tablet below the bust must, of course, ever claim regard for their references to the death of Shakespeare, but they are quite overshadowed in importance by the well-known inscription engraved on the stone slab that covers the tomb, since tradition has it that the lines were the composition of the poet himself, and penned,

very probably, when on his death-bed. They read as follows 1:

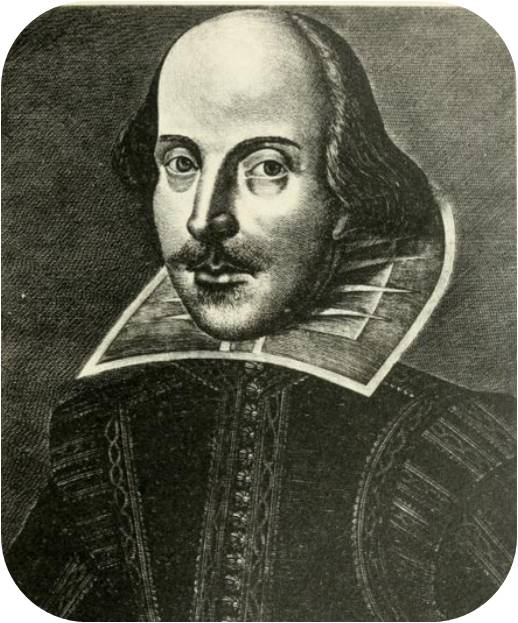

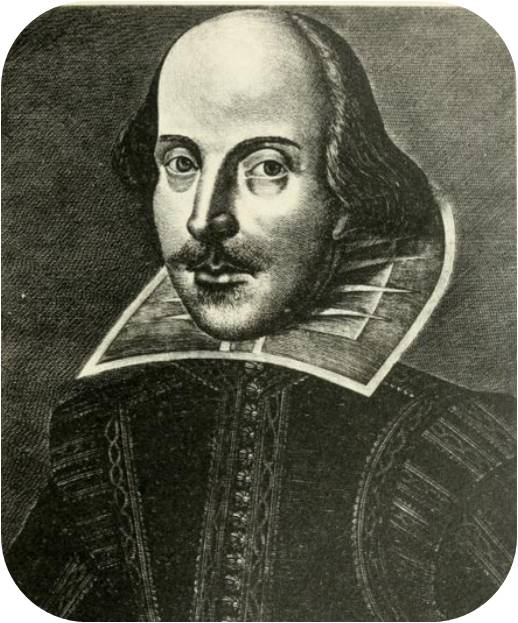

The 'Droeshout' Portrait

In point of intrinsic worth and literary interest the 'Droeshout' portrait of Shakespeare— an engraving of his likeness given to the world for the first time along with the

original edition of his collected works in 1623 — ranks next to the Stratford bust. Some authorities place what is known as the 'Chandos' portrait of the poet before the 'Droeshout'

print; while, again, others value the print even before the bust. But there are one or two good reasons why, in this particular instance, the work of the engraver should be more

highly valued than that of the painter. print; while, again, others value the print even before the bust. But there are one or two good reasons why, in this particular instance, the work of the engraver should be more

highly valued than that of the painter.

In the first place, the 'Droeshout' engraving was executed by a skilful artist whose profession it was to 'draw from the life'; whereas the 'Chandos' portrait is only supposed to

have been painted by one or other of two men whose calling was that of the player.

The 'Droeshout' engraving bears, in the second place, the special imprimatur of Shakespeare's associate, Ben Jonson; and not only his, but it also has the endorsement of the poet's intimate friends and 'fellows,' Heminge and Condell, who were remembered in his last will and testament.

In the third place, there is the suggestive fact that between the Stratford bust and the 'Droeshout' engraving there are certain striking correspondences, not so observable

between the bust and the 'Chandos' portrait, that have led the best authorities to infer that the sculptor of the bust in all probability had the engraving before him while executing

the details of his work, though modelling mainly from the mask taken after the poet's death. If that inference be correct, it again further shows that the 'Droeshout' print had received the approval of the poet's relatives, and also that Heminge and Condell obtained their sanction before affixing it side by side with Ben Jonson's dedicatory lines

in the forefront of the famous First Folio (1623). These lines declare as follows:

'To the Reader

This figure that thou here seest put,

It was for gentle Shakespeare cut,

Wherein the graver had a strife

With Nature, to out-do the life:

O could he but have drawne his wit,

As well in brasse, as he has hit

His face; the print would then surpasse

All that was ever writ in brasse:

But since he cannot, reader, looke

Not on his picture, but his booke.

B. J.'

In this work of Martin Droeshout there is nothing, beyond what the print itself bears, to tell of the circumstances in which it was originally executed. Assuming that other portraits of the poet were, in addition to this one, executed during his lifetime, the 'Droeshout' print was doubtlessly one of the earliest. Its date, however, is unknown. Judging from the appearance of the face generally, and comparing that with his other likenesses, Shakespeare

had not, it is pretty certain, attained his fortieth year when, with this portrait, "the graver had a strife With Nature."

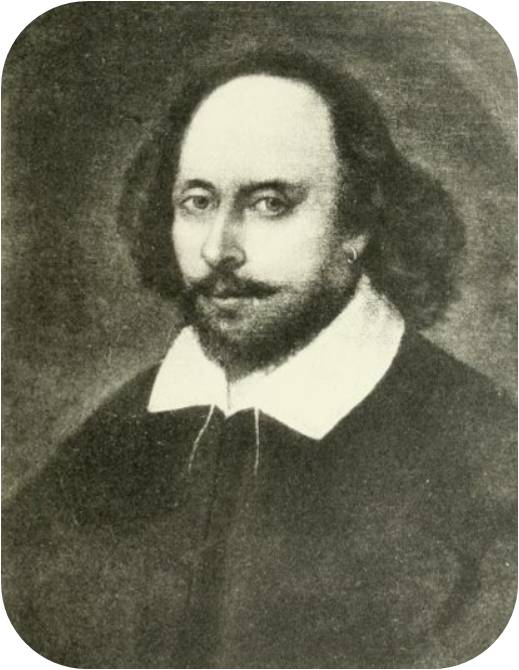

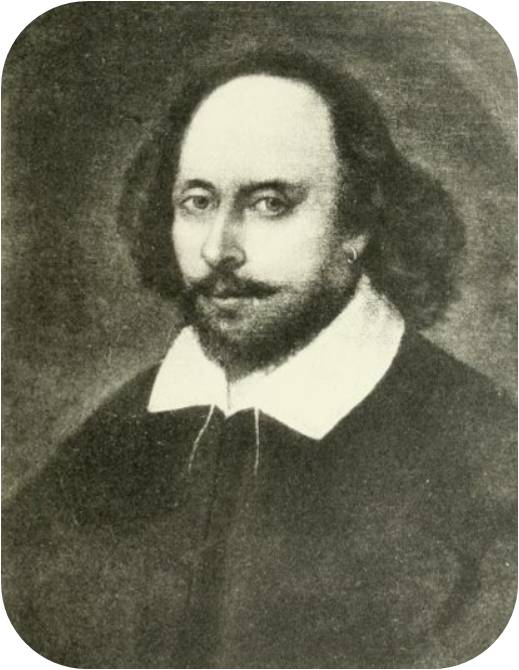

The 'Chandos' Portrait

Of the countless editions of the works of Shakespeare that show a frontispiece likeness of the poet, it is a singular fact that by far the greater number favour the 'Chandos'

portrait. The face and features of Shakespeare as 'imaged' in that portrait are those with which his readers are probably most familiar. It is not easy to account for this, since the

portrait is certainly not the first in point of genuineness, whatever may be its degree of artistic merit. Possibly it satisfies more fully the popular ideal of the likeness of a great

creative poet than does the bust or print just referred to. Be that as it may, the 'Chandos ' portrait, for various reasons, more than justifies its being kept in the custody of the

nation as a very rare and valuable relic of its greatest dramatist. Its history is, briefly, as follows. portrait is certainly not the first in point of genuineness, whatever may be its degree of artistic merit. Possibly it satisfies more fully the popular ideal of the likeness of a great

creative poet than does the bust or print just referred to. Be that as it may, the 'Chandos ' portrait, for various reasons, more than justifies its being kept in the custody of the

nation as a very rare and valuable relic of its greatest dramatist. Its history is, briefly, as follows.

According to the catalogue of the National Portrait Gallery, where the relic is now safeguarded, 'The 'Chandos' portrait was the property of John Taylor, the player, by

whom, or by Richard Burbage, it was painted. The picture was left by the former in his will to Sir William D'Avenant. After his death it was bought by Betterton, the actor, upon whose decease Mr. Keck, of the Temple, purchased it for forty guineas, from whom it was inherited by Mr. Nicholls, of Michenden House, Southgate, Middlesex, whose only daughter married James, Marquis of Carnarvon, afterwards Duke of Chandos, father of Eliza, Duchess of Buckingham.' Hence the name of the portrait, and such, in substance, is all that is known with certainty regarding its history.

The 'Jansen' Portrait

It is a remarkable circumstance that not a few of the likenesses of Shakespeare should have been executed by others than his own countrymen. As its name would seem to imply, the 'Jansen' portrait was the production of a foreigner. There are others, also, of the Shakespearean likenesses yet to be considered that owe their origin very largely to the skill of devout admirers of the poet who were not in any way of his national kith or kin. In the 'Jansen' portrait, so called from the name of the painter, Cornelius Jansen, it is quite possible that we have a picture of Shakespeare that shows him as he appeared about his forty-

sixth year, and when approaching, if not already arrived at, the summit of his physical and intellectual strength and glory. It is also possible that the likeness was painted as a

memento or token of that friendship and regard which were entertained for the poet by the Earl of Southampton almost from the outset of Shakespeare's career.

The 'Felton' Portrait

Apart from the question of authenticity, it is safe to say that the likeness of Shakespeare known under the name of the 'Felton Head' is one that will probably fascinate the

great majority of the poet's admirers more than any other portrait. It will, however, speak for itself as to this. But for a somewhat severe and sad, if not dissatisfied, look

that seems to haunt the eyes, the portrait takes rank, in at least its excellence of ideality, with any other example. Allowing for some exaggeration in the height of the forehead, a defect which has led some experts to infer that the 'Felton' portrait was in existence even before the 'Droeshout' print, and that, indeed, it served as the model for the engraver, it is assuredly a splendid portrait of Shakespeare, and

speaks eloquently of the painter's lofty conception of the

poet's features. Its history is curious, if for nothing more than the fact that the name, 'Gul Shakespear,' and the date, '1597,' together with the initials, R. B.,' traced on

the reverse side of the picture, indicate the likeness to have been, as some authorities believe, the handiwork of Richard Burbage, the player, who is thus for the second time

identified with his great contemporary in this interesting

connection.

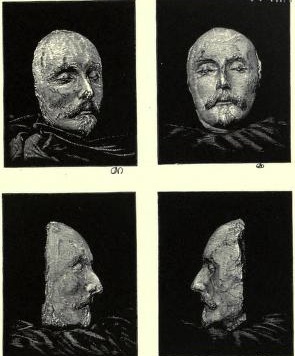

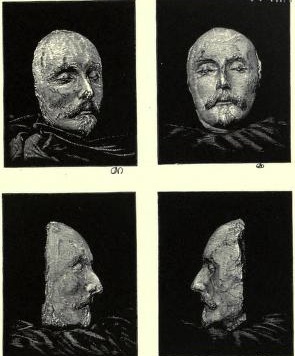

The 'Becker' Mask

In the year 1849 there was discovered at Mayence what bore to be a genuine though gruesome relic of Shakespeare, and claimed to be set almost side by side in value and interest

with the Stratford bust itself. This relic was declared to be nothing less than the mask of the face and features of the poet taken after his death in April 1616 (o.s.).

As nothing was

ever known as to what befell the mask after Gerard Johnson had manipulated it in the preparation of the bust — assuming it had been in his hands for that purpose — the finding of

such an extraordinary relic created widespread interest, not only throughout England and Europe, but in America, where also there were those who were ready to believe the

story.

As nothing was

ever known as to what befell the mask after Gerard Johnson had manipulated it in the preparation of the bust — assuming it had been in his hands for that purpose — the finding of

such an extraordinary relic created widespread interest, not only throughout England and Europe, but in America, where also there were those who were ready to believe the

story.

The resurrection of the veritable death-mask of the immortal author of Hamlet not unnaturally suggests, as it no doubt suggested at the time, a famous scene in the

last act of that famous tragedy. Nevertheless, its discovery was hailed with enthusiasm, and what purported to be an undoubted clue to a mystery more than two centuries

old was taken up at once and followed with rare persistence

by those who declared they held, in the possession of the

mask, the only key to its solution.

The gentleman into whose possession this curiosity came

was named Ludwig Becker, who, writing in 1850, gave so

entertaining an account of it as to induce Mr. Page, a well-known artist of New York, to visit Germany and there examine this famous relic for himself. After a prolonged

scrutiny of the mask, Mr. Page declared his firm belief in its genuineness, and thereupon made from it a very interesting set of models of the features of Shakespeare, which, at the

time, attracted great attention. An excellent account of the history of the mask was also written by Mr. Page for Scribner's Magazine of May 1876. The relic itself was

brought to London for exhibition, where it secured many

admirers and willing believers, and it is actually recorded

that some were so affected by the sight that they burst

into tears!

The 'Stratford' Portrait

Like the 'Becker' mask, the 'Stratford' portrait of Shakespeare, so called from its having been discovered in 1860 in that town, is quite a modern find. Whether the portrait had its original home in London or elsewhere is unknown; but, like the 'Becker' mask, it, too, was taken to the Metropolis for public exhibition. Many opinions were pronounced in favour of its genuineness, while many more unhesitatingly discredited it. At the time of its exhibition a newspaper warfare was waged over the question with results that, on the whole, were unfavourable to the pretensions of the portrait.

In this likeness Shakespeare appears as if in the very

flush and heyday of his early manhood and strength. A

robust, almost bucolic, massiveness and compactness is,

perhaps, the prominent physical trait. A calm, dignified

repose fills the full, winsome eyes, and at the same time

gently compresses the eloquent lips. The forehead is

ample: somewhat less lofty than in the bust, much less so

than in almost any other portrait, but still a fine, full, broad

brow that could only have been that of a highly gifted man.

Like so much else connected with Shakespeare, the history

of this portrait — when, and by whom, and for whom painted

— is unknown.

Some authorities believe it to have been the work of a

local artist, who either painted it to satisfy his own or

another's ideal. Some even incline to the view that it was

made to order, to do duty as a common tavern-sign! If

so, then it is surely one of the best examples of the kind ever

executed. After having been exhibited in London, the

picture was taken back to Stratford, where it has ever since

found a place of honour and safety.

The 'Hilliard' and 'Auriol' Miniatures

The former is by far the more interesting and meritorious.

When its pretensions to genuineness were put forward early

in the last century, the 'Hilliard' miniature belonged to

Sir James Bland Burges, Bart., who, in a letter to a friend

giving an account of it, alleged that it had been discovered

in a bureau which belonged to his mother, who had inherited it from her father, William Somerville the poet, and thus traced its history back to the days when the poet lived in

retirement at Stratford.

The 'Auriol' miniature is certainly more pretentious than the 'Hilliard,' though greatly inferior as a work of art or even as a likeness of the poet. It was claimed for it that it at

one time belonged to the Southampton family, but there is no evidence of this. It bears to have been painted when Shakespeare was in his thirty-third year, and it is recorded

that 'to the bottom of the frame of the miniature was appended a pearl, intended to infer that the original was a pearl of men.'

The 'Dunford' Portrait

If the likeness known as the 'Dunford' portrait has the slightest resemblance in any particular to Shakespeare, the individual must be exceptionally gifted who can trace it.

When its claims were put forward for the first time in 1815, Mr. Dunford, the owner, assured the public that he saw in the portrait a likeness to the "Droeshout" print.' Mr. Wivell, the well-known expert, compared them carefully and concluded that the resemblance was of the kind discovered by Fluellen between Macedon and Monmouth. When the portrait was exhibited shortly after its discovery in the year mentioned, it is recorded that 'of not more than six thousand

who went to see it, three thousand declared their belief in its originality.' Even an authority like Sir Thomas Lawrence voted in its favour. Moreover, it was twice engraved

by Turner in mezzotinto, so sincerely did many persons

believe in it as a true likeness of Shakespeare. Eventually,

however, it lost credit, and is now only remembered as an instance of that strange trait in the character of the British public, namely, its easy gullibility in matters appertaining

to Shakespeare.

Zoust's Portrait

An excellent likeness of the poet, which strikingly recalls the 'Chandos' portrait, is one that was alleged to have been painted by Soest, or Zoust. As that artist was not born

till 1635, when Shakespeare had been dead for nineteen years, his portrait must have been from a copy — probably that in the possession of Sir William D'Avenant, afterwards known as the 'Chandos' portrait.

How to cite this article:

Cargill, Alexander. Physiognomy and Portraits of Shakespeare. From Shakespeare the Player. London: Constable and company Ltd., 1916. Shakespeare Online. 20 Aug. 2009. < http://www.shakespeare-online.com/biography/portraitsfull.html >.

Note

1. Graphic added by Shakespeare Online editors (2014).

______

More Resources

Queen Elizabeth: Shakespeare's Patron Queen Elizabeth: Shakespeare's Patron

King James I of England: Shakespeare's Patron King James I of England: Shakespeare's Patron

The Earl of Southampton: Shakespeare's Patron The Earl of Southampton: Shakespeare's Patron

Going to a Play in Elizabethan London Going to a Play in Elizabethan London

The Shakespeare Sisterhood - A Gallery The Shakespeare Sisterhood - A Gallery

Worst Diseases in Shakespeare's London Worst Diseases in Shakespeare's London

Preface to The First Folio Preface to The First Folio

Shakespeare's Pathos - General Introduction Shakespeare's Pathos - General Introduction

Shakespeare's Portrayal of Childhood Shakespeare's Portrayal of Childhood

Shakespeare's Portrayal of Old Age Shakespeare's Portrayal of Old Age

Shakespeare's Attention to Details Shakespeare's Attention to Details

Shakespeare's Portrayals of Sleep Shakespeare's Portrayals of Sleep

Publishing in Elizabethan England Publishing in Elizabethan England

What did Shakespeare drink? What did Shakespeare drink?

Ben Jonson and the Decline of the Drama Ben Jonson and the Decline of the Drama

Publishing in Elizabethan England Publishing in Elizabethan England

Alchemy and Astrology in Shakespeare's Day Alchemy and Astrology in Shakespeare's Day

Entertainment in Elizabethan England Entertainment in Elizabethan England

London's First Public Playhouse London's First Public Playhouse

Shakespeare Hits the Big Time Shakespeare Hits the Big Time

|

More to Explore

Shakespeare's Parents Shakespeare's Parents

Shakespeare's Birth Shakespeare's Birth

Shakespeare's Siblings Shakespeare's Siblings

Shakespeare's Education Shakespeare's Education

Shakespeare the Actor Shakespeare the Actor

Shakespeare's Lost Years Shakespeare's Lost Years

Shakespeare's Marriage Shakespeare's Marriage

Shakespeare's Children Shakespeare's Children

Shakespeare's Burial Shakespeare's Burial

_____

|

Did You Know? ... Renaissance records of Shakespeare's plays in performance are exceedingly scarce. However, those few contemporary accounts that have survived provide brief yet invaluable information about a handful of Shakespeare's dramas. They give us a sense of what the play-going experience was like while Shakespeare was alive and involved in his own productions, and, in some cases, they help us determine the composition dates of the plays. Of all the records of performance handed down to us, none is more significant than the exhaustive diary of a doctor named Simon Forman. Read on...

|

_____

Was Shakespeare Italian? Was Shakespeare Italian?

How Many Plays Did Shakespeare Write? How Many Plays Did Shakespeare Write?

Shakespeare's Religion Shakespeare's Religion

Shakespeare's Contemporaries: Top Five Greatest Shakespeare's Contemporaries: Top Five Greatest

Shakespeare's Audience: The Groundlings Shakespeare's Audience: The Groundlings

Four Periods of Shakespeare's Life Four Periods of Shakespeare's Life

Shakespeare's Language Shakespeare's Language

Words Shakespeare Invented Words Shakespeare Invented

Shakespeare's Reputation in Elizabethan England Shakespeare's Reputation in Elizabethan England

_____

Bard Bites ...

Elizabethan playhouses were open to the public eye at every turn, and scenery could not be changed in between scenes because there was no curtain to drop. Read on...

____

Most early editors removed five lines from Romeo and Juliet for the sake of common decency. Which lines caused such scandal? Find out...

____

The Elizabethans tried to cure this frightening disease with the inhalation of vaporized mercury salts. Read on...

|

_____

Shakespeare at the Globe Shakespeare at the Globe

Shakespeare's Impact on Other Writers Shakespeare's Impact on Other Writers

Quotations About William Shakespeare Quotations About William Shakespeare

Shakespeare's Boss: The Master of Revels Shakespeare's Boss: The Master of Revels

Daily Life in Shakespeare's London Daily Life in Shakespeare's London

Life in Stratford (structures and guilds) Life in Stratford (structures and guilds)

Life in Stratford (trades, laws, furniture, hygiene) Life in Stratford (trades, laws, furniture, hygiene)

Stratford School Days: What Did Shakespeare Read? Stratford School Days: What Did Shakespeare Read?

Games in Shakespeare's England [A-L] Games in Shakespeare's England [A-L]

Games in Shakespeare's England [M-Z] Games in Shakespeare's England [M-Z]

An Elizabethan Christmas An Elizabethan Christmas

Clothing in Elizabethan England Clothing in Elizabethan England

|

print; while, again, others value the print even before the bust. But there are one or two good reasons why, in this particular instance, the work of the engraver should be more

highly valued than that of the painter.

print; while, again, others value the print even before the bust. But there are one or two good reasons why, in this particular instance, the work of the engraver should be more

highly valued than that of the painter.

portrait is certainly not the first in point of genuineness, whatever may be its degree of artistic merit. Possibly it satisfies more fully the popular ideal of the likeness of a great

creative poet than does the bust or print just referred to. Be that as it may, the 'Chandos ' portrait, for various reasons, more than justifies its being kept in the custody of the

nation as a very rare and valuable relic of its greatest dramatist. Its history is, briefly, as follows.

portrait is certainly not the first in point of genuineness, whatever may be its degree of artistic merit. Possibly it satisfies more fully the popular ideal of the likeness of a great

creative poet than does the bust or print just referred to. Be that as it may, the 'Chandos ' portrait, for various reasons, more than justifies its being kept in the custody of the

nation as a very rare and valuable relic of its greatest dramatist. Its history is, briefly, as follows.

It is believed that when Shakespeare died, on the 23rd April 1616 (o.s.), exactly fifty-two years of age, a cast of his features was taken— by whom is not known, though the

name of the sculptor of the bust, Gerard or Gerald Johnson, a Hollander, has been suggested. Johnson has been credited with having done his part of the work well, since, before its

erection in the chancel of the church, the bust was probably approved by Shakespeare's relations as a good likeness, and deemed worthy of its conspicuous position and of the man

it represented. As is well known to all who have seen the bust, its prominent characteristic is the calm serenity and gentleness of the expression of the features, an expression

that fairly well satisfies the popular ideal of England's

greatest poet.

It is believed that when Shakespeare died, on the 23rd April 1616 (o.s.), exactly fifty-two years of age, a cast of his features was taken— by whom is not known, though the

name of the sculptor of the bust, Gerard or Gerald Johnson, a Hollander, has been suggested. Johnson has been credited with having done his part of the work well, since, before its

erection in the chancel of the church, the bust was probably approved by Shakespeare's relations as a good likeness, and deemed worthy of its conspicuous position and of the man

it represented. As is well known to all who have seen the bust, its prominent characteristic is the calm serenity and gentleness of the expression of the features, an expression

that fairly well satisfies the popular ideal of England's

greatest poet.

As nothing was

ever known as to what befell the mask after Gerard Johnson had manipulated it in the preparation of the bust — assuming it had been in his hands for that purpose — the finding of

such an extraordinary relic created widespread interest, not only throughout England and Europe, but in America, where also there were those who were ready to believe the

story.

As nothing was

ever known as to what befell the mask after Gerard Johnson had manipulated it in the preparation of the bust — assuming it had been in his hands for that purpose — the finding of

such an extraordinary relic created widespread interest, not only throughout England and Europe, but in America, where also there were those who were ready to believe the

story.